Preview of Phaedra’s Love, Yale Summer Cabaret

The Yale Summer Cabaret prepares to open its final show of the 2016 season, this Thursday. Co-artistic Jesse Rasmussen, who opened the season with a highly physical adaptation of Alice in Wonderland in June, will close out the season directing renowned playwright Sarah Kane’s “brutal comedy,” Phaedra's Love.

Kane’s plays are known for their uncompromising approach to a world in which humanity is prone to violence and, in her more reflective works, suffers from the anxieties of its condition. The “darker facets” of theater attract Rasmussen, who feels Phaedra's Love is a suitable follow-up to Alice, where “the gently dark elements invited” the “playfulness”—with an edge of psychosis—that marked the Summer Cab’s opener. Rasmussen, who will direct the Jacobean tragedy, ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore as her thesis project next spring, says “an interest in violence” links modern writers like Kane and Edward Bond, whose work she also considered as a summer project, with the Jacobean sense of the dramatic use of extreme violence on stage.

Jesse Rasmussen

Asked why violence should be a necessary element of the plays she directs, Rasmussen said “turn on the news,” and spoke eloquently about how it’s “irresponsible to not connect” theater to the stories of random violence and assault that have made 2016 so stressful. Rasmussen, whose background includes extensive avant-garde work with Four Larks, a theater group that “creates contemporary performance at the intersection of theatre, music, visual art, and dance,” is drawn to work that takes chances and creates a unique theatrical experience.

That said, Kane—whose most divisive work was Blasted—called Phaedra's Love “my comedy,” and, indeed, Rasmussen says, it is the playwright’s most accessible and classical work, having been commissioned as a reworking of Seneca’s Phaedra. So there are familiar elements right off—first, “an intimate family drama that eventually explodes,” and the Greek "myth Kane is riffing on.” The myth concerns the story of how a curse on Phaedra, wife of King Theseus and step-mother to Hippolytus, causes her to lust after her step-son, bringing about his death and, in some versions, her own suicide. What Kane brings to this situation, in a play originally staged in the 1990s, is her “deep repulsion” at her countrymen’s obsession which the British royal family which, at the time, included Princess Diana.

Part of the challenge Rasmussen sees is in rendering the play’s corrosive sense of monarchy “in a way that will be legible here” in the U.S. Certainly, celebrity worship and what Rasmussen calls “the sort of useless leaders paid to be photographed” are not unfamiliar to us, nor is the gap between rich and poor that, if bad enough in the ‘90s, is likely worse now. What’s more, the recent fulminations for Brexit by those who demand a more insular Britain should give Kane’s attack on privileged crassness plenty of bite.

Rasmussen sees the play as “formally exciting,” in part because the violence, which happens offstage in the Greek play, is “in our faces” in Kane’s version, since the playwright’s aesthetic intent is to make the audience “witnesses to violence.” Thus, another challenge of the play is the logistics of staging violence. Rasmussen and her team have had many conversations about violence and witnessing as aspects of the play, which, Rasmussen says “pulls no punches.” Beginning with “the internal domestic space” of this particular family, Kane includes the populace, so that there is an enlarged sense of representation in the play’s conclusion. As Rasmussen says, “there are lots of ways blood can come out on stage,” and part of the task she has undertaken is “do violence well and real” within the limited, and extremely intimate, Yale Cabaret space. To that end, Rasmussen is again working with choreographer Emily Lutin, who she worked with on her studio project, Macbeth, to incorporate with precision and sensitivity the physical process of violence her cast will enact.

The play’s formal challenges are supported by Kane’s poetic use of language. For Rasmussen, the playwright is “a master of economy” who uses truncated syntax to “cut the fat” from dialogue, which makes her play rich and exciting for actors. Kane’s style, Rasmussen has found, promotes attention to detail so that the difference in pause between a comma and a period can be highly expressive. The play’s protagonist, Hippolytus “is a horrible person,” but ends up being “the most honest.” Played by Niall Powderly—who played the title role in Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus last summer—Hippolytus, in the director’s view, emerges as the “moral compass of the play, unexpectedly.”

In fact, one reason Rasmussen picked this play over others was because she likes “plays with some type of love story” in them. She found herself fascinated by Phaedra: “how could this woman be in the horrifying position” of such inappropriate desire? Phaedra, played by Elizabeth Stahlmann, who played the title role in Sarah Ruhl’s Orlando last summer, harbors a love for her stepson that makes her “lead with her loins.” “Stepmothers aren’t generally liked” in literature, Rasmussen points out, and so the notion of Phaedra as a sympathetic character may well have been what drew Kane to the myth. Our culture is “still terrified at the idea of a transgressive woman,” so that Phaedra’s sexuality, for Rasmussen, can be seen as heroic in its honesty, and “a transforming element” that “lights a fire that burns down the palace, so to speak.” Theseus, played by Paul Cooper, who played the White Knight and White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, is the proverbial absentee husband, setting up a situation where Phaedra decides she “won’t deny herself and live quietly.”

The play, considered Kane’s wittiest, benefits from the detachment that mythic characters possess for contemporary audiences, even if tellingly modernized. And it’s no accident that Rasmussen’s three principles—Powderly, Stahlmann and Cooper—are the three actors who worked with her in David Harrower’s poetic and unsettling play of triangular passion, Knives in Hens, in the Cabaret last fall. “I would only work on this play with actors who I’ve worked with and who I know trust me,” Rasmussen says, “before essentially pushing them off a cliff.”

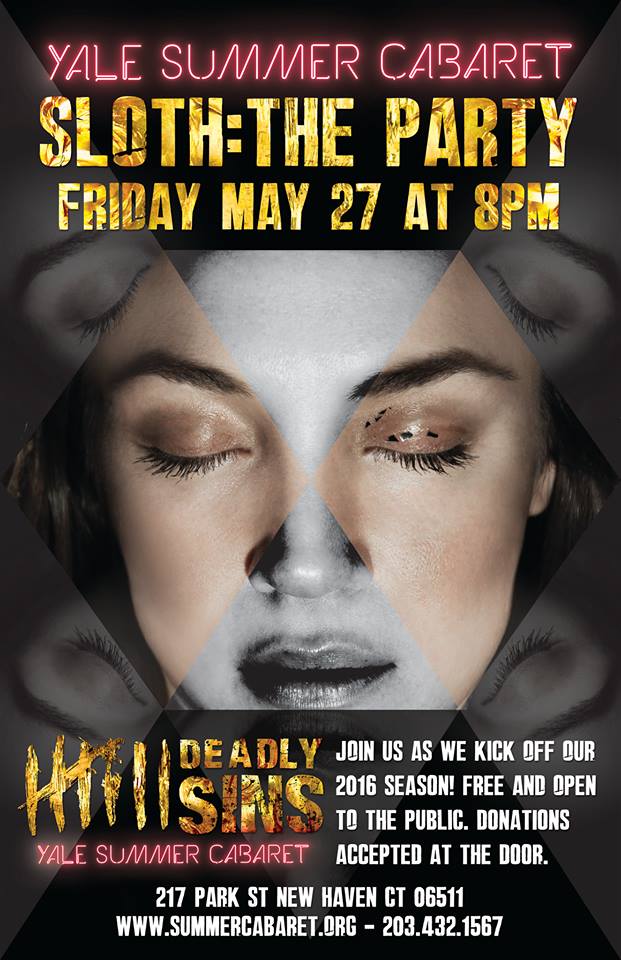

It’s been a season of sin at the Yale Summer Cabaret, and—after sloth, gluttony, greed, wrath and envy, it’s time for lust—able, here, to “mutine in a matron’s bones,” to borrow Hamlet’s line—to inspire what may be the most challenging play of the four presented this summer. While not a large ensemble of many parts, Phaedra's Love will challenge in a different way: most of the scenes are “two-handers” so that we will be spending time with characters who develop over the course of the evening through specific dramatic pairings.

Sex, violence . . . lust, murder . . . a dysfunctional family in a dysfunctional society. And, yes, laughs.

Phaedra’s Love

By Sarah Kane

Directed by Jesse Rasmussen

Yale Summer Cabaret

August 4-14, 2016