Preview, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, New Haven Theater Company

If you’re a regular at New Haven Theater Company shows, you might remember the time the company built what looked to be a functional luncheonette in their theater space in the back of English Building Markets. That was George Kulp’s set for William Inge’s Bus Stop, which he directed. Last year, there was the set for Neil Simon’s Rumors that turned the space into a two-story living room with numerous doors to slam. That was Kulp’s too.

Beginning this Thursday and running for the next three weekends, the space will be the dayroom at a mental hospital where a host of inmates live placid lives under the purview of a controlling nurse as Kulp directs NHTC’s next offering, Dale Wasserman’s stage adaptation of Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Kulp, who says this is “the most ambitious and challenging” play he’s directed yet, seems to like plays with a lot of characters and a very focused set.

If you were around in the 1970s, you no doubt remember the film version of the novel, directed by Milos Forman, which won Oscars for picture, director, actress (Louise Fletcher as Nurse Ratched), and actor (Jack Nicholson as Randle Patrick McMurphy), and adapted screenplay. Indeed, the role of McMurphy was easily the most famous of Nicholson’s impressive career—until he took an ax to a bathroom door in The Shining.

McMurphy is a boisterous ne’er-do-well who considers a stint in a mental hospital preferable to prison. His fellow inmates are an odd assortments of “lifers” who prefer the hospital to trying to get along in the outside world. And Nurse Ratched is there to make sure everything runs the way she likes. The confrontations between McMurphy and the nurse become a battleground over the quality of life. In the film, you just have to root for McMurphy as Fletcher’s version of the nurse is so inhumanly impersonal.

Kulp is wary of expectations derived from the film. First of all, the film was adapted from the novel, not from Wasserman’s play. And, while the drama’s trajectory runs much the same, the filmed versions of certain characters sometimes aimed for comic caricature. Kulp stresses that his cast is “very careful” to avoid that pitfall, and that means creating useful backstories for the characters to give them fuller dimension. Which might be a way of saying that Kulp is urging them to put some method in the madness.

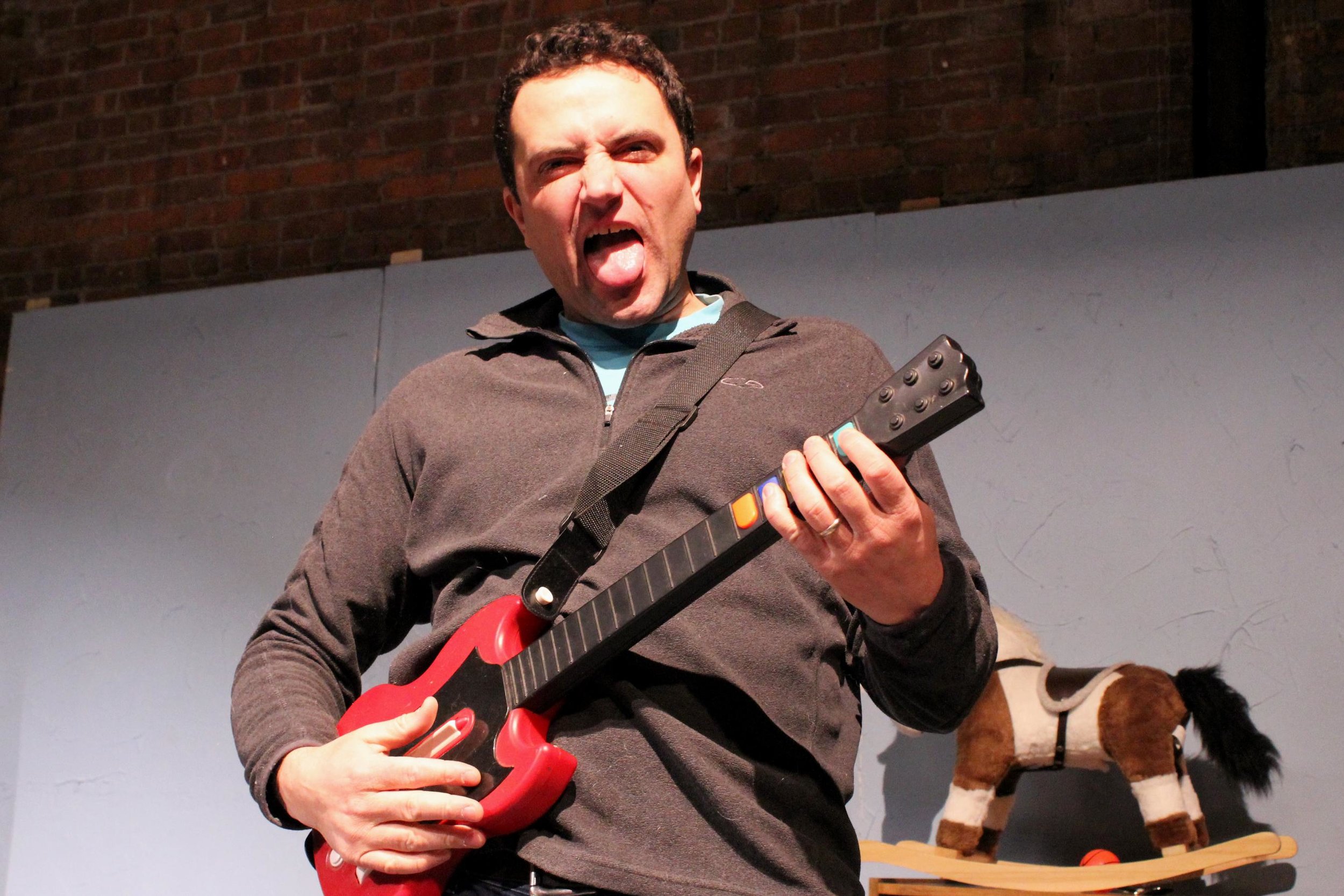

McMurphy will be played by Trevor Williams who directed NHTC’s previous offering, Marjorie Prime. Williams acted under Kulp’s direction as the naive cowboy, Bo Decker, in Bus Stop and was one of the two hitman in Harold Pinter’s The Dumb Waiter last season, directed by John Watson. McMurphy’s nemesis, the maternal Nurse Ratched, will be played by Suzanne Powers, who worked with Kulp in Rumors.

Other NHTC members on hand include John Watson as Dr. Spivey, who tends to back the authoritarian nurse; Erich Greene, the other hitman in Dumb Waiter, as Cheswick, an anxious patient; and J. Kevin Smith, the obstreperous neighbor in Rumors and the boozing professor in Bus Stop, as Harding, the patient with the most self-control.

That leaves many parts featuring actors who will be appearing in a NHTC production for the first time, though, in most cases, Kulp has worked with each before. They include: Al Bhatt, Tristan Bird, Ralph Buonocore (who appeared in NHTC’s Urinetown), Robert Halliwell, Ash Lago, Empress Makeda, Joseph Mallon, Jodi Rabinowitz, John Strano, and Aaron Volain.

For Kulp, much of the challenge, with so many characters “and so much going on”—including a basketball game—is to keep the play “moving at the right pace.” His approach, he said, is to tell his actors “to go for the moon and then pull back.” The casting is key and his previous experiences with the cast make for a lot of trust.

The play was chosen in part because of its name recognition, its diverse cast, and because, Kulp said, it’s “an entertaining and timely story to tell.” He suggested that the issue of how our society treats mental illness and the play’s convincing sense of “the misuse of authority” are meaningful in our time, as they were when the novel was published in 1963 and when the film version was released in 1975, both key works of the Vietnam era of American culture.

Is it “cuckoo” to place such a largescale play in the New Haven Theater Company’s intimate space? Get your tickets and find out (the play is running for three weekends rather than two because seating is limited).

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

By Dale Wasserman, from the novel by Ken Kesey

Directed by George Kulp

New Haven Theater Company

April 25-27, May 2-4, May 9-11

For tickets and info, go here

See my review here