As Steve Scarpa, of the New Haven Theater Company, sees it, Thornton Wilder is “our own.” And if that’s so, his town is our town. That play, one of the truly iconic American plays, is the latest project of the NHTC. Scarpa, who directed the play before in Shelton, finds himself now, five years later, reflecting on how the play’s big theme is the “idea of memory.” And, on that note, it’s worth remembering that Wilder is buried in his family plot in Mt. Carmel Cemetery, marked only by a little plaque, that he graduated from Yale in the class of 1920, that he lived for several decades in our environs (Hamden), and that he was a three-time Pulitzer Prize winner and that his classic play, which treats American small-town life sub specie aeternitatis, is, this year, 75 years old.

That’s kind of hard to believe, since the play, in some ways, seems like it should date back much further—to the Twenties, at least, even to the previous century—but, in fact, Our Town represents ideas that Wilder was picking up from that era—the period of late Modernism—including the style of Gertrude Stein’s cubist masterpiece The Making of Americans, and the meditation on the changing same that is James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, then known as “Work in Progress.” Wilder was an early enthusiast of Joyce’s work and penned an essay about it. The idea of evoking a place—for Joyce, Dublin, for Wilder, Grover’s Corner, New Hampshire—through a historied sense of time is a common feature that shows the modernist influence in Wilder’s best-known work.

In staging the play, Scarpa finds himself more than ever aware of how New Haven, where he was born, has changed in his own lifetime, making Our Town’s sense of both a place’s permanence and impermanence very much a hometown concern. As Scarpa sees it, Wilder’s play is about a place that could be any place, but that doesn’t make the town a generic Anytown, U.S.A. Rather it’s a universal place, and reminds us that, no matter where we hail from, we remember a place through a particular sense of time.

For the New Haven Theater Company, that sense of time and place is also important. The close-knit group has lived and worked together for some time now—more than one married couple can be found in the cast, and, in the case of the Kulps, their daughter is also involved. That means the generational sense so important to the play is not only thematic, it’s also an element of the company. That feature of NHTC is important to Scarpa, for, though this production does include non-members who auditioned for parts, the company’s ensemble sensibility—that sense of short-hand between actors who know each other well—makes his job easier and more fun. Fun that extends to the audience—many the friends, families, and co-workers of the NHTC actors, in their regular lives—who can look forward to seeing who so-and-so is this time.

One interesting element of the casting: The Stage Manager—the part Wilder himself played and which is perhaps best known as a vehicle for Hal Holbrook—will be played by a woman: Megan Chenot. Scarpa finds that the change in gender gives the play a different tone—more engaging and personable—but that it also makes the Stage Manager’s managing of Emily’s marriage a more nuanced occasion. The play, Scarpa stresses, isn’t as sentimental as maybe our own memories—many of us read it or saw it produced in high school—make it out to be, and that means adapting the play to our time may well be in order.

Scarpa hit upon the idea of doing the play while researching Wilder’s papers in the Beinecke for an article about New Haven turning 150. That piece provoked another, in the Arts Paper, about Wilder, and the idea of re-staging the play came from there. The New Haven Theater Company tends to be a shape-shifting affair without a permanent performing space, and finding the right spot can be a chore. This time they’ve been able to use a big, empty room at the back of English Building Market, next to the Institute Library, on Chapel Street, a location that is not only a bit of New Haven history but which, by virtue of the antiques and heirlooms it sells, offers a serendipitous step into memories of other times.

Drew Gray, relative new-comer to NHTC, is responsible for transforming the room into a stage-set. Gray expected an easy task as the play famously asks for “no design” and is meant to be a theatrical space, such as would be found in any real theater. Not being in a theater, per se, means “something needs to be there,” Gray says, and he hit upon the idea of musical notes. Music is directly referenced in the play, such as the hymn “Blessed Be the Tie that Binds,” and Gray set out to create “abstract shapes to sculpt the space” so as to recall music.

Gray has also incorporated ideas he first encountered in Super Studio, a conceptual design studio in the 1970s. Their idea of “life without objects” is one that Gray finds serviceable in his design concept where most of the setting takes place in the mind, not in actual furniture and props. He has introduced two ten-foot columns or pillars to break up the space and, with changes in lighting, create shadows for effect. It’s a case of making “the scenery disappear into the scenery” Gray says, and that sounds high concept enough to serve both the modernism of Wilder’s vision as well as its timeless sense of classical civilization.

Both Scarpa and Gray stress that Wilder was about more than just making a feel-good paean to Americana. The play, Scarpa says, is “both funnier and sadder” than many viewers might expect, and that the NHTC’s effort is to “make something beautiful” that will live up to Wilder’s intention to add America’s “moral, decent” values to what Wilder saw as the long march through history to civilized behavior.

Given that Wilder first staged the play 75 years ago—in 1938—with the world on the bring of World War II, it’s worthwhile to reflect on how far along we are on that march, now.

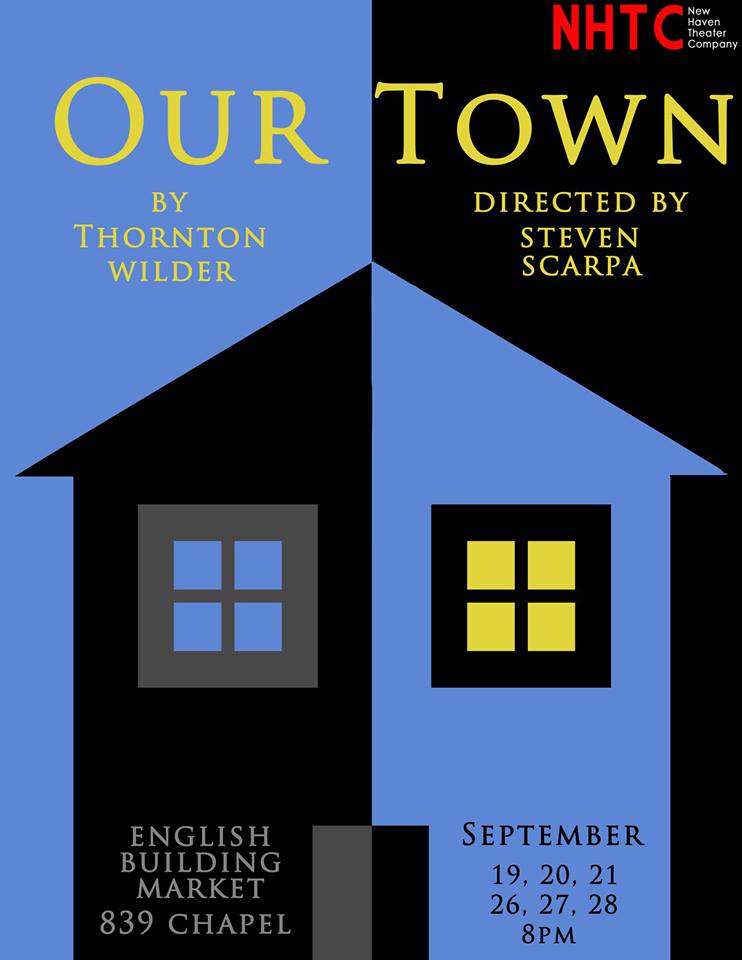

Our Town by Thornton Wilder Directed by Steve Scarpa

English Building Market, 839 Chapel Street September 19, 20, 21, 26, 27, 28 8 p.m.