Review of Falsettoland, Music Theatre of Connecticut

Falsettoland, now playing at Music Theatre of Connecticut through November 21, directed by Kevin J. Connors is a quirky, sappy, funny, tear-jerker of a musical. And how many shows can you say that about?

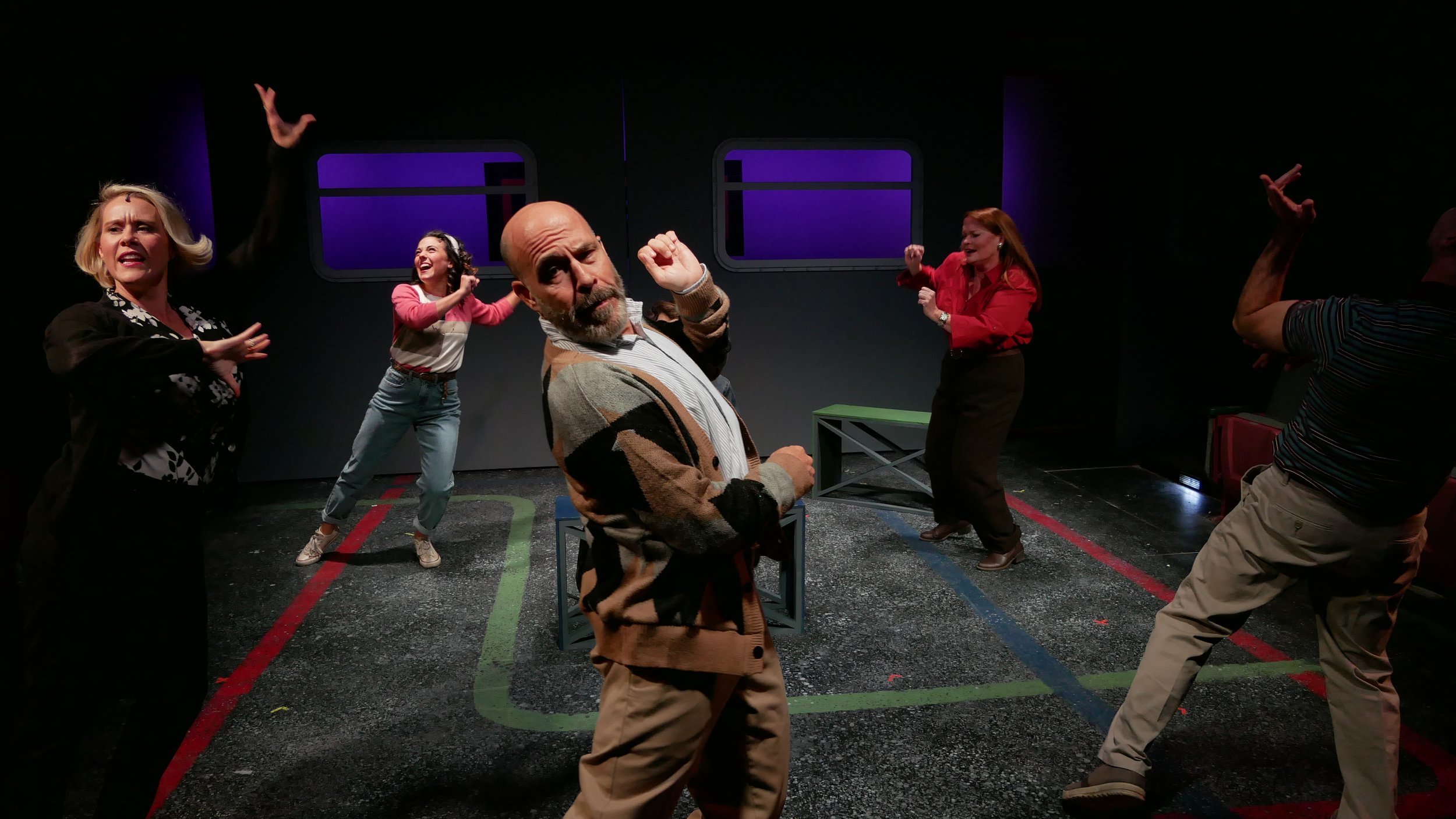

The cast of the Music Theatre of Connecticut production of Falsettoland, directed by Kevin Connors; photo by Alex Mogillo

What’s it about? Well, really it’s about love, but the context for the vicissitudes of love involves gays and straights, Jews and a few non-Jews. The show’s humor is decidedly arch—as for instance in both versions of “the Miracle of Judaism” or in “Baseball Game” or “Everyone Hates Their Parents”—and its play upon our sympathies stems from our acceptance that—to vary Tolstoy—“all dysfunctional relationships are unique in their dysfunction.” For Marvin (Dan Sklar) the dysfunction is starting to double-down. In the first part of Falsettos—Falsettoland is the second half of the longer musical—he left his wife, Trina (Corinne C. Broadbent), for his lover Whizzer (Max Meyers). As Falsettoland opens, Marvin and Whizzer have split up and Trina has taken up with Mendel (Jeff Gurner), Marvin’s former psychiatrist. Then there’s the looming Bar Mitzvah for Jason (Ari Sklar), the son of Marvin and Trina who misses Whizzer and invites him to his baseball game, to the awkwardness of all. For Marvin, some kind of reckoning must be coming, but—as the song “Something Bad is Happening” late in Act One implies—he hasn’t yet seen the worst of it.

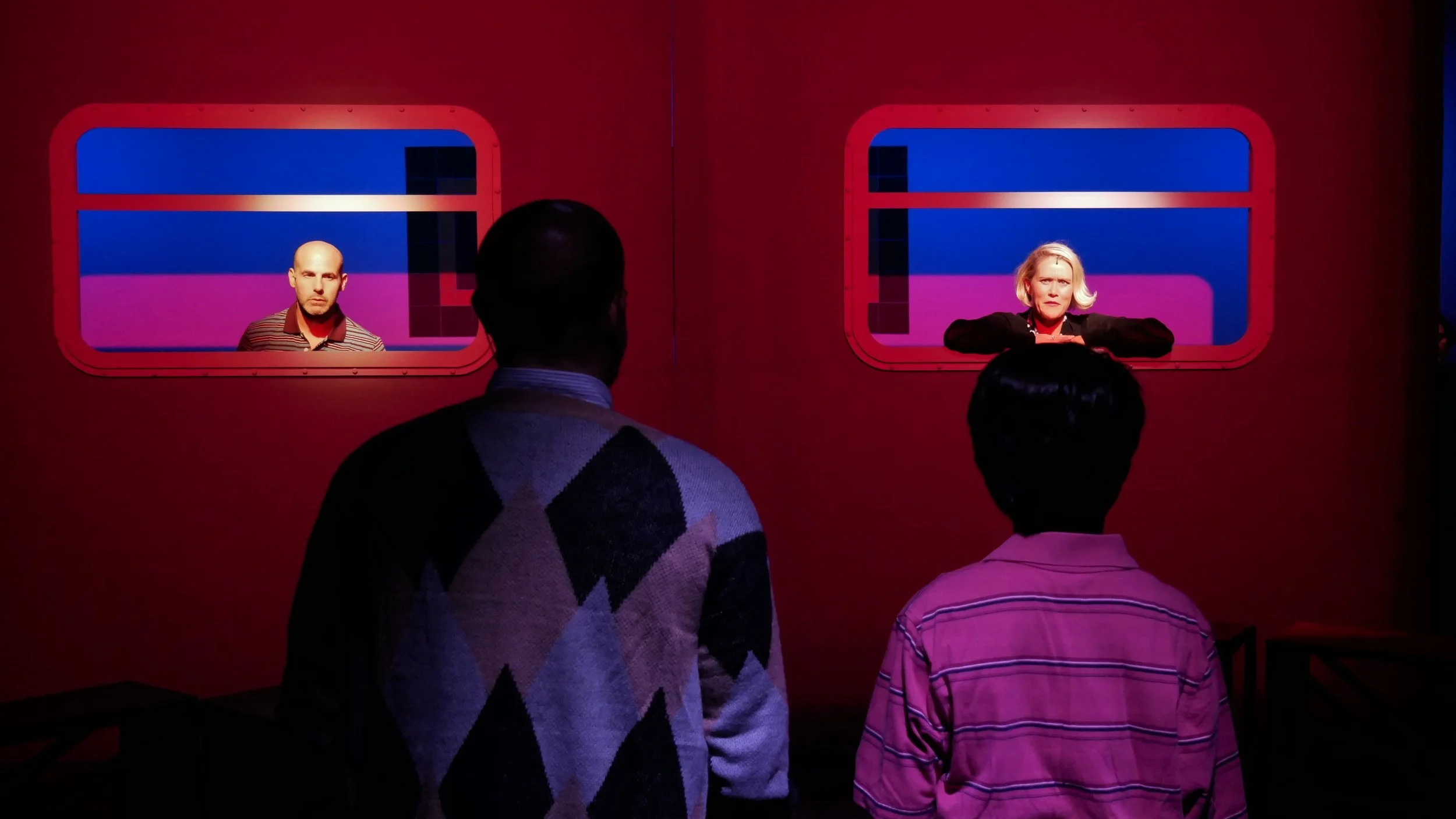

The cast of Falsettoland, Music Theatre of Connecticut, left to right: Trina (Corinne C. Broadbent), Mendel (Jeff Gurner), front, Cordelia (Elissa DeMaria), back, Marvin (Dan Sklar), front, Dr. Charlotte (Jessie Janet Richards), back; photo by Alex Mogillo

The cleverness of the show’s book—by James Lapine and William Finn—lies in how its mundane situations spark asides and reflections and confrontations, all of which are sung as dialogue. The music and lyrics by William Finn have a savvy, wry reflectiveness and bounce along with an agreeable forthrightness that seem in-keeping with the “tell it to a psychiatrist” tone. The shrink—played with crusty affability by MTC regular Gurner—is almost like a stand-in for the audience, a bit off to the side and yet emotionally involved. And that would also seem to be the point of the lesbian couple—Dr. Charlotte (Jessie Janet Richards) and her partner Cordelia (Elissa DeMaria), a non-Jew obsessed with Jewish cuisine; they might be the “zany neighbors,” but in fact, like us, they are drawn-in and play audience to the family dysfunction that, at first, seems only to hang on the question of how Marvin will navigate the emotional ties that bind him, and, more crucially, how Jason will manage to have a Bar Mitzvah he can tolerate or maybe even be proud of. But as “Unlikely Lovers,” a highlight of Act Two, makes clear, the scope of the foursome comprised by Dr. Charlotte, Cordelia, Marvin and Whizzer is key to the play’s vision of how new loves form in the space once dominated by family ties.

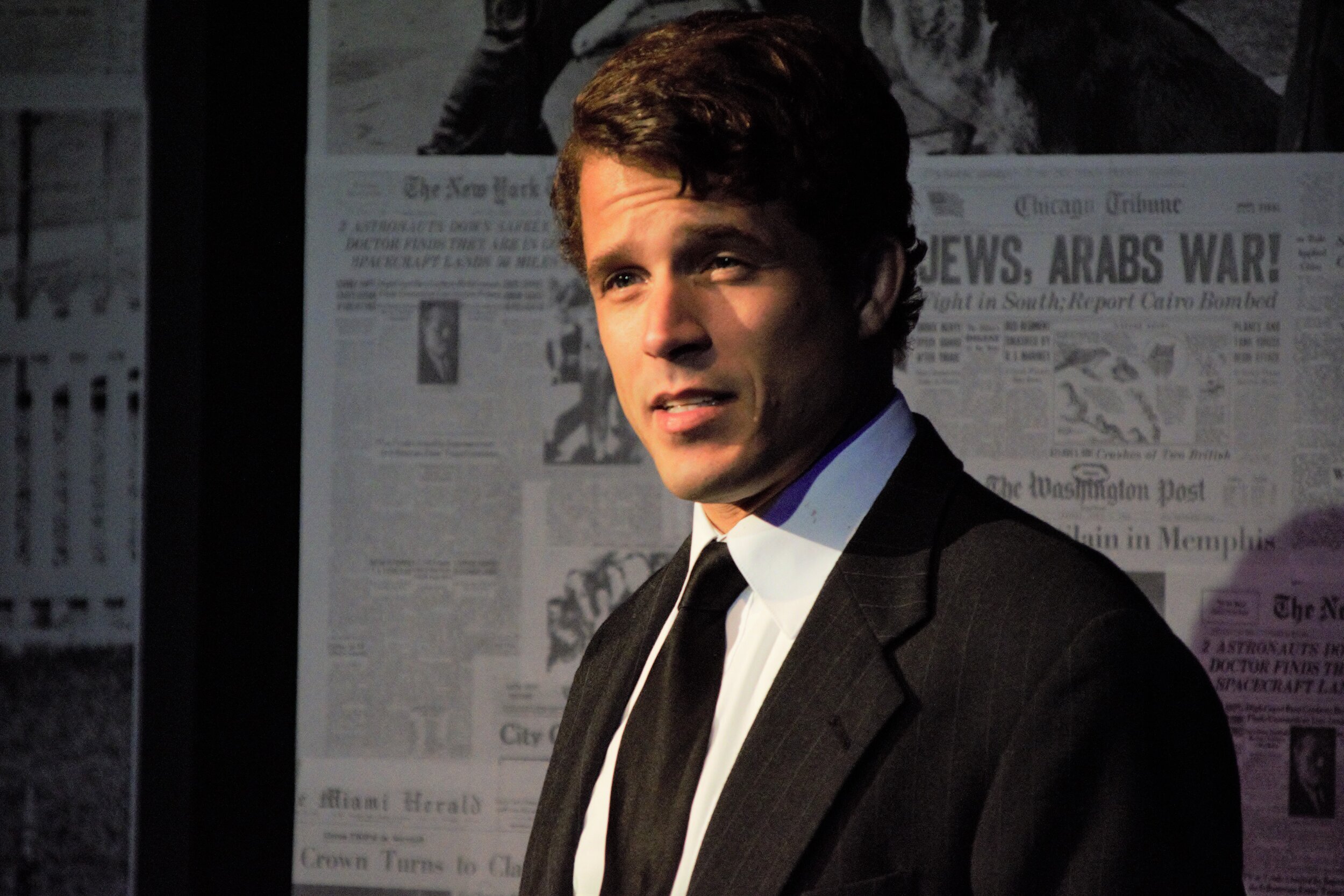

Whizzer (Max Meyers) and Marvin (Dan Sklar) in the MTC production of Falsettoland; photo by Alex Mogillo

But that’s not to say that more traditional family ties are given short shrift. Key to the tone the play strikes is the role of Trina. She might be more freaked out than she is, she might also be way more resentful of her former husband’s love for a man and her son’s friendship with that man, and she could whine a lot more. The great thing about Corinne C. Broadbent’s rendering of Trina is that she’s not melodramatic nor particularly long-suffering. Her big number in the second act, “Holding to the Ground” (sung while doing her aerobic exercises) lays out her emotional parameters and it’s one of the strongest numbers, matched—or even topped—by Max Meyer’s strong delivery of Whizzer’s “You Gotta Die Sometime.” What these two sung speeches give is not only insight into the difficult terrain these characters are navigating but also show them coping and revealing strengths that take us beyond the play’s tendency to use quirks for laughs.

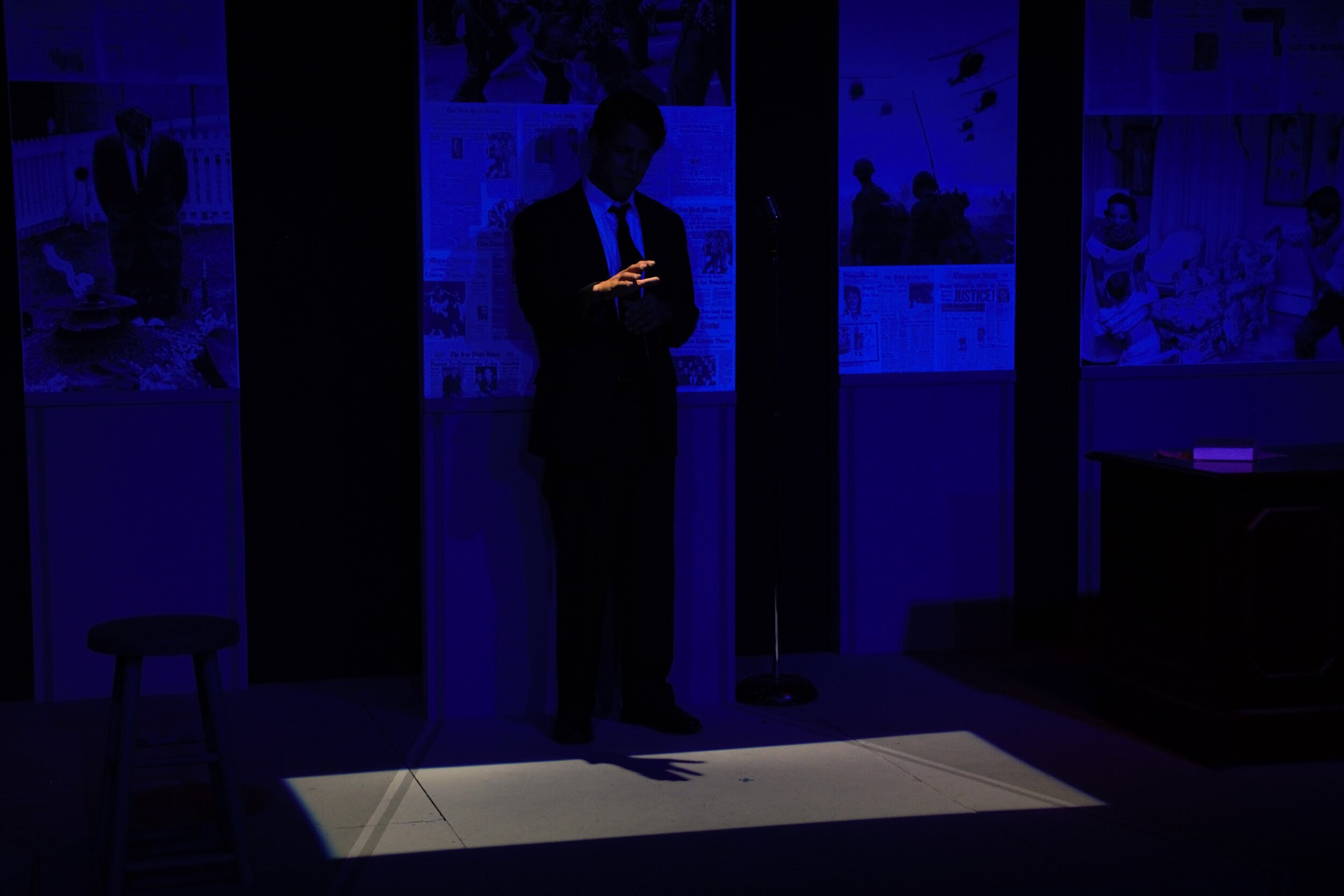

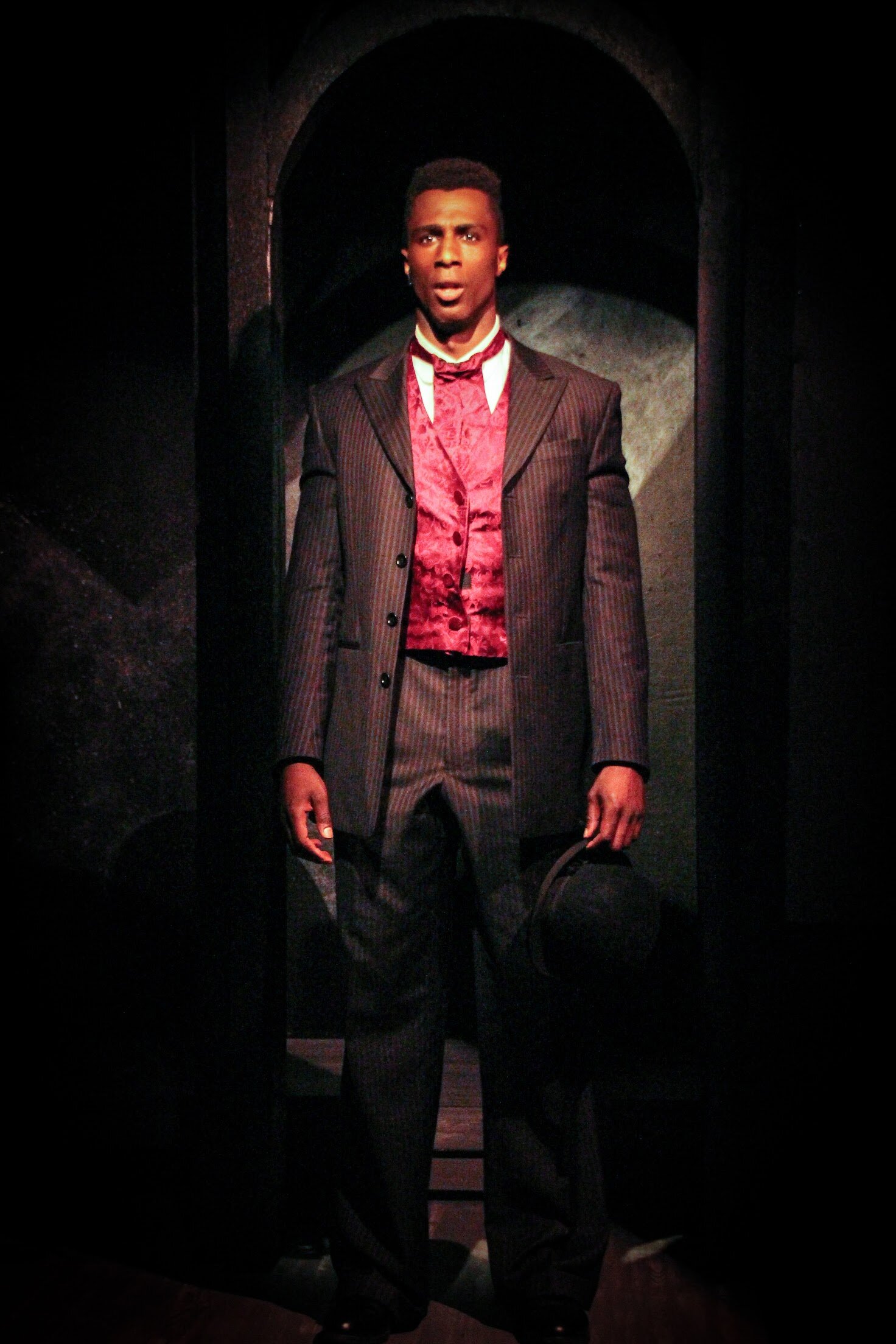

the cast of Music Theatre of Connecticut’s production of Falsettoland, directed by Kevin Connors; photo by Alex Mogillo

At the heart of it all is Sklar’s Marvin, a likeable guy dealing with a lot; you might even say he’s a bit of a schlemihl trying to be a mensch. His genuine affection for Whizzer wins us over in “What More Can I Say,” and the real nature of the problem facing the couple ratches up the drama and takes us back to very stressful times that the musical aims to revisit as a coping exercise. And so, in good uplifting-ending fashion, the fate of that Bar Mitzvah is to reinforce the growth all the characters have undergone. Amongst all the good work done here—including Lindsay Fuori’s subway car set that adds the right note of urban landscape—special mention should be made of Ari Sklar’s Jason who is such a natural for this part it’s as if it’s a slice of his life. That illusion is helped by the fact that Jason’s father, Marvin, is played by Ari real life dad. Family ties, after all.

Marvin (Dan Sklar), Trina (Corinne C. Broadbent), background; Mendel (Jeff Gurner), Jason (Ari Sklar), foreground; photo by Alex Mogillo

In revisiting those days of something awful in Falsettoland, the MTC production might be said to sound a note of nostalgia. Bad as things got, there was a sense that that they could only get better—in part through visions like Finn and Lapine’s of the everydayness of same-sex couples as part of the same old traditions grown so familiar. One of those miracles of humanitarianism.

The cast of Music Theatre of Connecticut’s production of Falsettoland, directed by Kevin Connors; photo by Alex Mogillo

Falsettoland

Book by William Finn and James Lapine

Music and Lyrics by William Finn

Directed by Kevin J. Connors

Scenic Design: Lindsay Fuori; Lighting Design: RJ Romeo; Costume Design: Diane Vanderkroef; Sound Design: Will Atkin; Prop Design: Sean Sanford; Stage Manager: Jim Schilling; Choreography: Chris McNiff; Musical Direction: David John Madore

Cast: Corinne C. Broadbent, Elissa DeMaria, Jeff Gurner, Max Meyers, Jessie Janet Richards, Ari Sklar, Dan Sklar

Musicians: Piano/Musical Director: David John Madore; Drums: Steve Musitano, Chris McWilliams

Music Theatre of Connecticut

November 5-21, 2021