Review of Escuela at Yale Repertory Theatre

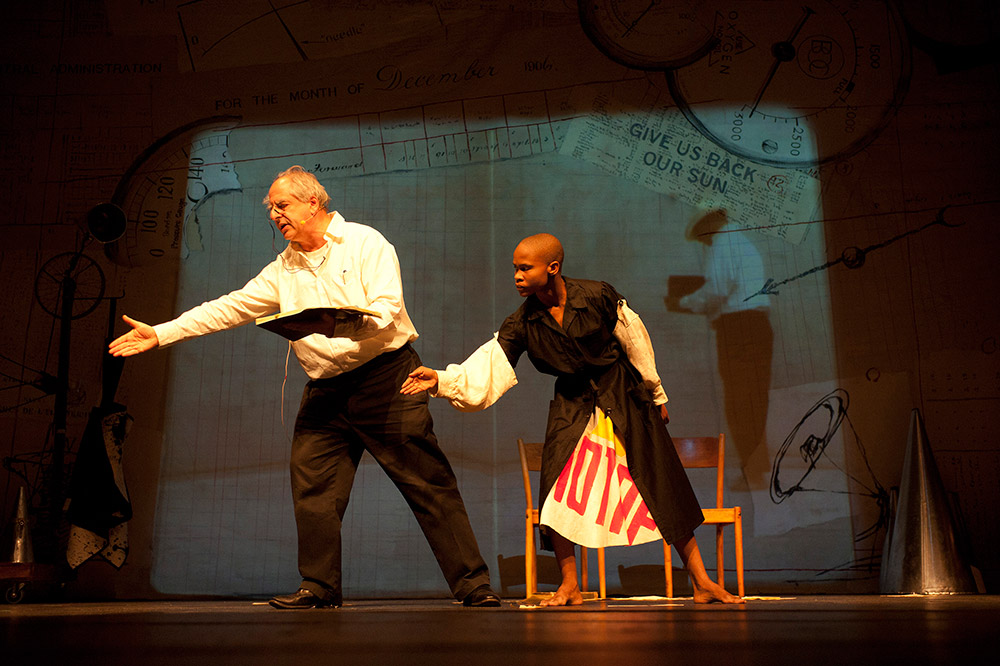

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to join a cell committed to revolutionary violence, check out Guillermo Calderón’s Escuela, playing for three nights at the Iseman Theater as part of the Yale Repertory Theatre’s No Boundaries series. Calderón both wrote and directs the play, whose title is simply “School” in Spanish, as a means to present a generation of activists in 1980s’ Chile largely ignored now because of their willingness to resort to terrorist violence to overthrow the brutal regime of Augusto Pinochet. The five member cast—two men, three women—enact both the roles of instructors or experts and of students as they move through such topics as correct handgun protocol, how to plant a bomb and light its fuse, how to identify and counteract psychological warfare, and how it is that capitalists control everything.

As the cast wears scarves that mask their faces throughout the play and speak in Spanish with English subtitles, audiences can expect a bit of alienation. Happily, though, the stringent, didactic tone of the lessons is easied by odd, off-beat bits of human curiosity, vanity, naïvete. First of all, there’s something inherently hopeless in the methods—as in knocking out electricity in the slums so that the police won’t come in—and something misguidedly heroic, or laughably uncertain, about key instructions: “how far should we run after lighting the fuse?” “As far as you can.” Or when the handgun expert coolly demonstrates how to kill three adversaries armed with guns firing hundreds of rounds as though choreographing a scene in a Lethal Weapon movie with himself as hero.

But the comedy of what almost seems a support group for folks with revolutionary proclivities only appears fitfully. At other times the songs sung—as in “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh”—and the shared ethos evoked might also create a creeping memory of the era when the Weatherman or the Baader-Meinhof group grabbed headlines by trying to bring down the authorities—aka “the Pigs” (and sure enough one instructor draws a police-pig on the chalkboard)—upon their committed, anarchic activities. Somewhere between those days, in which the radical Left struggled against the mainstream forces of oppression, and events such as the Oklahoma City bombing, or the bomb at the Boston Marathon, the opprobrium upon violent tactics as inherently terrorist, in the name of no matter what cause or gripe, has undermined the romance with revolution that, perhaps, Escuela wants to revisit.

Transposed from Chile, where it should remind some of a past they may have forgotten and instruct the young about what went down, Escuela might easily provoke censure from a civic mind-set that repudiates the ethics of violent overthrow, but, if so, it must be allowed that Calderón is clear about the banality of evil. The characters in his play are clearly not villains, if only because they seem so obvious about their misgivings and off-hand attempts at solidarity.

With a blackboard, a slide projector, a handgun, a bomb prop, and a guitar, the five conspirators seem exemplars of both the basis of revolutionary acts as well as the virtues of basic theater. And as theater, Escuela has its virtues, though its pacing, like a late night class, feels at times a bit pro forma, as if the students themselves are being attentive out of politeness rather than zeal. One would welcome some raised voices of disagreement or more tension caused by fear or by stronger versus lesser opposition, if only for the sake of drama. There are subtle differences among the conspirators but one would be hard-pressed to break through the anonymity they see as a means to escape identification.

And maybe it's true that a theater, like a politics, that relies upon heroes and leaders and self-involved characters is unlikely to ever achieve a breakthrough for the good of all. In Escuela, the lesson, as theater, as politics, is more nostalgic than revolutionary, seeming to belong to what was rather than shaping what may be coming.

Escuela

Written and directed by Guillermo Calderón

Assistant Director: María Paz González; Design and Technician: Loreto Martínez; Musical Arrangements: Felipe Borquez; Tour Manager: Elvira Wielandt

Performers: Camila González Brito; Luis Cerda; Andrea Laura Giadach Cristensen; Carlos Ugarte Díaz; Francisca Lewin

Yale Repertory Theatre

February 24-26, 2016