Federman's Last Laugh

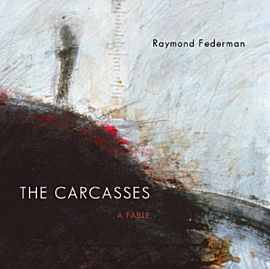

Raymond Federman’s last novel, Shhh: A Story of Childhood, forthcoming from Starcherone Books, is excerpted here with a piece called “List of Scenes of My Childhood To Be Written.” Federman died last October, shortly after BlazeVox published his novella, The Carcasses, which, for this reader, brought to mind The Tibetan Book of the Dead (or my personal preference, Book of Natural Salvation) and Kafka’s Parables and Paradoxes as well as some of his other short work.

In The Carcasses, Federman’s narrator has the “FNACS” (the afterlife’s revolutionary forces) taking up what has traditionally been Satan’s rebellious role in Heaven by calling for a democratic transmutation of the dead—politicizing metamorphosis, the apparent essence of nature itself.

The Carcasses is not a human-centered fable. It’s not even biocentric, since there’s just as great a likelihood that at some point in one’s eternity those who’ve passed on will come back to this dimension as a piss pot. The novella’s flexible topology, its permeability of self, the apparent possibility of its imaginary carcass narrator’s future enlightenment (or is it escape?) from karma, its wheel of life, make Federman’s novel a pleasure to read. And in the end, when facing transmutation, these feelings about civil rights among the dead seem irrelevant. Too much freedom and freedom becomes meaningless, an emptiness that seems a death itself. A carcass with too much freedom is, perhaps, too much a carcass. One who’s free of one’s self is without self.

We laugh at all this death because we’re dying ourselves, which means we’re alive. It’s seems grief can tickle our funny bone. Why? What does it say about us that we can laugh at death?

In The Carcasses, one sees mind, matter and energy seeking to sustain their interrelated disequilibria for as long as possible, creating an unsentimental journey with a dash of Calvino’s “lightness,” a bit of Laurence Sterne the Psychonaut resisting his uncarcassization…forever digressing because the novella’s ending is the carcass's ending…

Unlike The Carcasses,Federman’s last story, Shhh: A Story of Childhood, seems from the brief yet tantalizing excerpt as posted an ever-playful, ever-youthful spirit looking back, planning ahead despite the fact…despite the unspeakable…laughing…

I was one of Raymond’s students at SUNY Buffalo in the mid-1990s and was quite surprised when, in one of our last email exchanges before he died, he offered that Proust had influenced him more than Beckett. He’d barely mentioned Proust in the fifteen years we’d known each other. He said I should read Proust if I wanted to know what he meant. I recently began following that advice, and one of the first things I came across, while doing some preliminary reading, was Proust’s alleged statement that "An hour is not merely an hour, it is a vase full of scents and sounds and projects and climates."

The excerpt of Shhh is a list of things to do, an imperative litany fleshing out memory before it slips forever into the past tense, beginning with his Uncle Leon’s planting a tree, his digging in the yard, a metaphor for Federman’s digging through memory, planting and dispersing seeds in the mind evolving into word-beings that populate a living text…a family tree…and in less than an hour Federman makes a universe of memories that never were, memories of senses left un-sensed…in a vase, or urn.

Federman’s list of things to do is a list of things never done, the outline of some unspeakable undone, knowing that if not for the Holocaust, these word-beings would have been people who would have, like us, had sex with themselves and others, congregated for various reasons, become excited over political ideas and whatnot, etc. & so forth. They would have lived messy lives, like us…no better, no worse...mois…nous.

This list of 33 imperatives perhaps signifies "Solomon's Seal" or the "Star of David," a mature family tree that never bloomed except in these stories, and in Federman’s mind where his imagination lived for them and words became beings. The ninth item is, perhaps, the most poignant if the reader’s aware of Federman’s actual biography and the myth Federman created through fifty years of critifiction, surfiction, and laughtrature. It’s here where his family leaves Paris, rather than staying as they actually did, when the Nazis invaded.

Then, three points later: “Scene demonstrating how verisimilitude often becomes improbable when one tells a story.”

Feel the fiction of the fiction to your bones.

I have a feeling that Shhh: A Story of Childhood might be my favorite of all Federman’s books, but I’ll have to wait and see like everyone else.

And that’s hard.