Coming to Yale Cabaret . . .

Now previewing Yale Cabaret shows for the rest of the semester and into January—Cab 4 through 10. The Artistic Directors Hugh Farrell, Tyler Kieffer, Will Rucker, and Managing Director Molly Hennighausen have joined forces, reviewed the applicants, and determined upon the following, an eclectic mix of the new, the untried, the recent, the experimental—even, perhaps, the confrontational. Here we go:

Cab 4: Rose and the Rime, a play by Nathan Allen, Chris Mathews, Jake Minton; directed by Kelly Kerwin, a third-year dramaturg.

Kerwin was an Artistic Director at last year’s Cab, and a director and developer of the very popular We Know Edie La Minx Had a Gun, and this time she’s directing and choreographing a show that features dance, song—with the vocal talents of Andrew Burnap, whose singing graced Why Torture is Wrong . . . in the first show of the last Summer Cab—and original music. The show, which was first developed in the House Theatre of Chicago, features a cast of 9 to tell this modern myth in which a plucky young girl (Chalia La Tour, who is on a roll this semester) sets off on a quest to free the town of Radio Falls, Michigan, from a permanent blizzard visited upon it by the Rime Witch. Because the eternal winter trope graces “The Snow Queen” fairytale, the show is open to comparisons with the most successful animated film of all time, Disney’s Frozen. OK, fine, so come on and see what’s different. October 16-18.

Now previewing Yale Cabaret shows for the rest of the semester and into January—Cab 4 through 10. The Artistic Directors Hugh Farrell, Tyler Kieffer, Will Rucker, and Managing Director Molly Hennighausen have joined forces, reviewed the applicants, and determined upon the following, an eclectic mix of the new, the untried, the recent, the experimental—even, perhaps, the confrontational. Here we go:

Cab 4: Rose and the Rime, a play by Nathan Allen, Chris Mathews, Jake Minton; directed by Kelly Kerwin, a third-year dramaturg.

Kerwin was an Artistic Director at last year’s Cab, and a director and developer of the very popular We Know Edie La Minx Had a Gun, and this time she’s directing and choreographing a show that features dance, song—with the vocal talents of Andrew Burnap, whose singing graced Why Torture is Wrong . . . in the first show of the last Summer Cab—and original music. The show, which was first developed in the House Theatre of Chicago, features a cast of 9 to tell this modern myth in which a plucky young girl (Chalia La Tour, who is on a roll this semester) sets off on a quest to free the town of Radio Falls, Michigan, from a permanent blizzard visited upon it by the Rime Witch. Because the eternal winter trope graces “The Snow Queen” fairytale, the show is open to comparisons with the most successful animated film of all time, Disney’s Frozen. OK, fine, so come on and see what’s different. October 16-18.

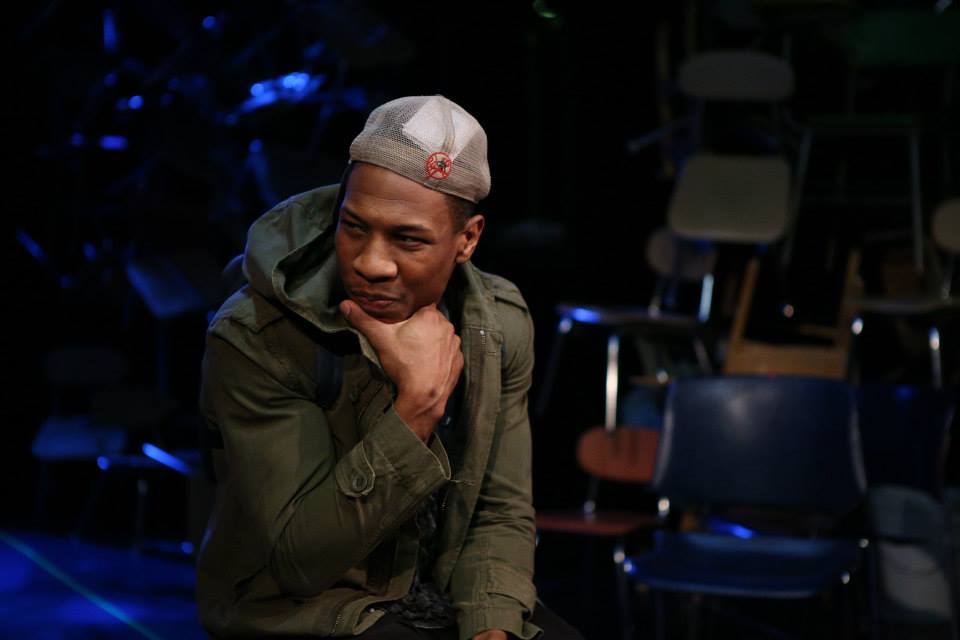

Cab 5: Touch, a play by Toni Press-Coffman; directed by Elijah Martinez, a second-year actor. Newish playwright Press-Coffman brings us a tale about loss and bereavement, couched in cosmic terms. It’s also a play with a four-person cast that starts with a mammoth monologue that will be fielded by second-year actor Jonathan Majors, a major factor in the success of The Brothers Size at the close of last year’s Cab season. The script riffs on Keats and the stars and the infinite expanse that pretty much identifies as “the Romantic Sublime.” Directed by Martinez, who was also an asset in The Brothers Size and a strong presence in the most recent Summer Cabaret. October 23-25.

Cab 6: Hotel Nepenthe, a play by John Kuntz; directed by Rachel Carpman, a third-year dramaturg. Poe fans no doubt recognize “nepenthe” as the stuff the speaker of “The Raven” is supposed to “quaff” so as to “forget the lost Lenore.” Keep that in mind, because Kuntz’s play, which debuted at the Huntington Theater in Boston in 2012, is about a “nebulous hotel” where lots of things are going on and—as was said by Scatman Crothers’ character in The Shining—“not all of them was good.” Four actors play four characters each in this feast of off-beat characterization that, the press release says, is a “hilariously horrific play” “where strangers tangle themselves” in mysteries and “wind up covered in whipped cream.” November 6-8.

Cab 7: MuZeum, a play by Raskia and Sumedh; translated and directed by Ankur Sharma, a special research fellow in directing. The horrendous rape and murder of a woman on a bus in South Delhi, India, in 2012, inspires this play, a journey through the history of the treatment of women in India, from the celebrated goddesses of myth, to the colorful heroines of Bollywood extravaganzas, to street victims of mutilation and rape. Co-Artistic Director Hugh Farrell says this is the show he’s “probably most excited about in [his] entire life,” as it captures the realities of India in ways not generally seen in the West or acknowledged by India itself. A Brechtian theater-piece based on contemporary incidents with a cast of 3 female actors as the women speaking their own truth. November 13-15.

Cab 8: Solo Bach, conceived and directed by Yagil Eliraz, a second-year director. Violinist Zou Yu of the Yale School of Music undertakes to play live two Bach pieces for violin each show; before our eyes these pieces are interpreted by 4 performers—2 male, 2 female—who “represent” the different voices of the violin through patterns of movement. Featuring a startling set with use of scrims, this unique production should be a feast for eyes and ears, as the visual and the aural work together in concert to the sublime measures of Johann Sebastian Bach. December 4-6.

Cab 9: The Zero Scenario, a play by third-year playwright Ryan Campbell; directed by Sara Holdren, a third-year director. In last year’s Cabaret, they brought us the outrageous tale of Joan of Arc in the Space Age in A New Saint for a New World, and this time Ryan Campbell and Sara Holdren are back with a “sci-fi comedy” that features 6-ft. field tics, a boyfriend along on a mysterious roadtrip his girlfriend instigates, and the question “can you terrify people in the theater”? Starring Ariana Venturi, who shone in the first two shows of the Yale Summer Cabaret. December 11-13.

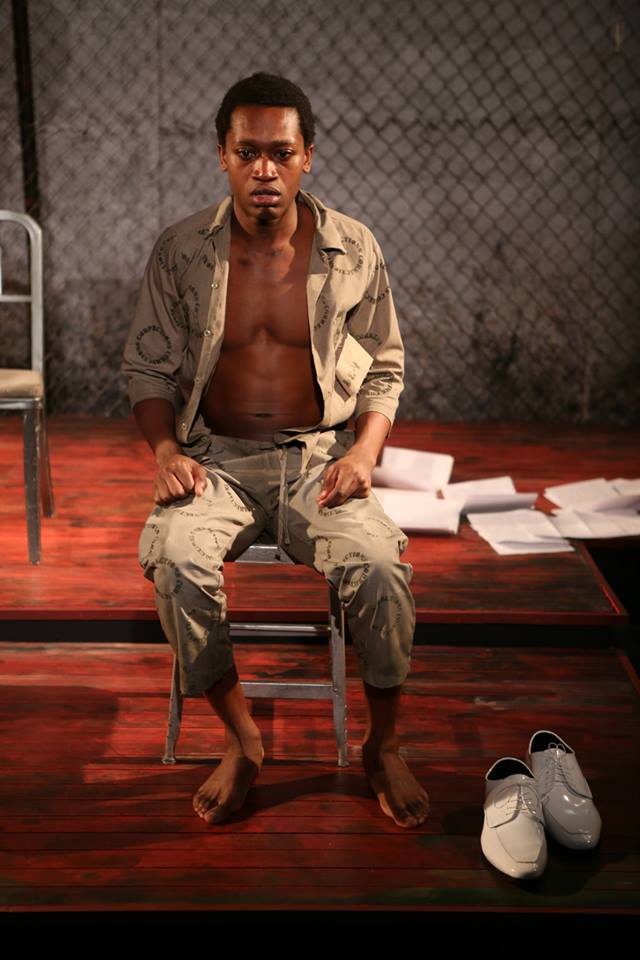

Cab 10: 50:13, a play by Jireh Holder, a second-year director; directed by Jonathan Majors, a second-year actor. What does that title mean? It’s a ratio. 13% of males in the U.S. are African-American; 50% of males in U.S. prisons are. This important theater-piece looks at that disparity through the eyes of the incarcerated, using oral histories to tell the story of Dae Brown who, in three days, tries to impart all he knows about being a man to a teen inmate serving an adult sentence. January 15-17.

That's what's on the way. See you at the Cab!

Yale Cabaret 217 Park Street For more information and tickets and menus: Yale Cab