Sexual Politics

Review of Cloud 9, Hartford Stage

Caryl Churchill’s wildly irreverent and comic play Cloud 9 addresses sexual politics, and how mores change with the times. It also shows how the past—here, the British past, specifically—is always being re-imagined. Act One’s lively burlesque of Victorian erotic relations in the 1870s is paralleled with a rather more naturalistic rendering set in 1979 in Act Two. The play dates from 1979, so Act Two, originally, was very contemporary indeed. The main difficulty now is that we’ve almost gotten to the point at which “the 1970s” may inspire a burlesque spirit similar to what Churchill makes of the 1870s. If played more for laughs—such as its invocation of a New Agey “goddess”—Act Two might have more bite. In any case, its effort to imagine a sort of social utopia of sexual relations and child-rearing may strike some as quaint, others as progressive—even now. Or especially now?

Lin (Sarah Lemp), Victoria (Emily Gunyou Halaas) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Which is a way of saying that the past’s social progress can still present a challenge in times of virulent conservatism. In any case, Cloud 9 remains a challenging and amorphous play that provides equal parts entertainment and food for thought. Launched initially as Margaret Thatcher came to power, Cloud 9 may make us oddly nostalgic for the hopes of earlier eras.

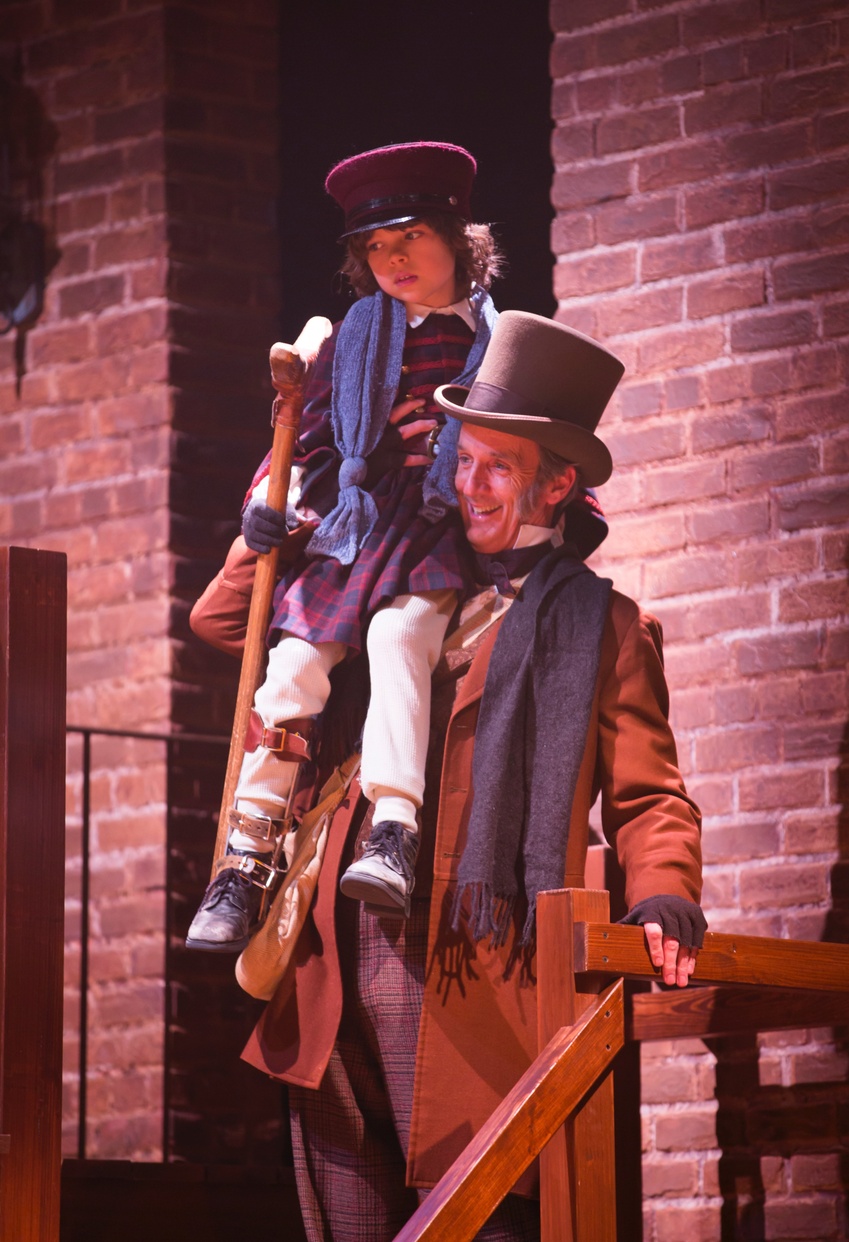

Cathy (Mark H. Dold) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Casting is key to the success of the production at Hartford Stage, directed by Associate Artistic Director Elizabeth Williamson, in her directorial debut. Because the cast of seven actors must play the 15 characters of both acts—in some cases cross-gender and contrary to age—and because who doubles as whom is established by Churchill, the overall effect depends upon actors who can manage the considerable disparity in roles. Here, Mark H. Dold enacts the most striking transformation, setting the tone for both acts. In Act One, he plays the repressive patriarch Clive, looking and sounding very Victorian indeed, then plays a preening little girl, Cathy, in Act Two; in both cases, Dold’s character lords it over the others. That shift is the most telling in this play of shifting orientations, and Dold carries it off splendidly.

Front: Edward (Mia Dillon), Betty (Tom Pecinka), Joshua (William John Austin); Rear: Ellen (Sarah Lemp), Clive (Mark H. Dold), Maud (Emily Gunyou Halaas) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Act One takes us to a colonial outpost in South Africa where Clive resides with his family: demure wife Betty (Tom Pecinka), adolescent son Edward (Mia Dillon), who has a penchant for playing with dolls, baby Vickie (who is a doll), and mother-in-law Maud (Emily Gunyou Halaas); there’s also a manservant Joshua (William John Austin), who has renounced his people through his attachment to Clive; a maid, Ellen (Sarah Lemp), who is very affectionate toward Betty; Mrs. Saunders (Lemp again), a very independent widow; and a very manly explorer, Harry Bagley (Chandler Williams). The amusement is in seeing how a surface “normality” is constantly undermined by the kinds of subversive urges that, time was, would’ve been the subject of considerable repression. Comic moments, such as Ellen’s attempt to seduce Betty, and Harry misreading signals from Clive, are set against bits that are almost poignant, such as Joshua’s song at Christmas, a plaintive love note to his oppressors. Mia Dillon, a veteran actress, is quite remarkable as little Edward, and Tom Pecinka languishes quite ladylike as doleful Betty.

In Act Two, Cathy’s winsome childishness is the best feature, as the play’s treatment of the problem of parenting, as an ongoing chore without nursemaids to take up the slack, hits a contemporary note. Cathy’s mother is Lin (Sarah Lemp), a lesbian with eyes for Victoria (Emily Gunyou Halaas), the doll grown up, we’re to imagine, who has a son we never see and whom she is attempting to raise with help from her novelist husband, Martin (Chandler Williams). Martin is a nice send-up of the "enlightened" male of the period, no less overbearing than Clive, but in a more sensitive way, trying to be supportive and to share parenting duties and the like. His hair and clothes recall aspects of the 1970s most of us would rather forget. Gunyou Halaas, in contrast, wears her retro threads quite well and portrays Victoria as a woman on the verge of change.

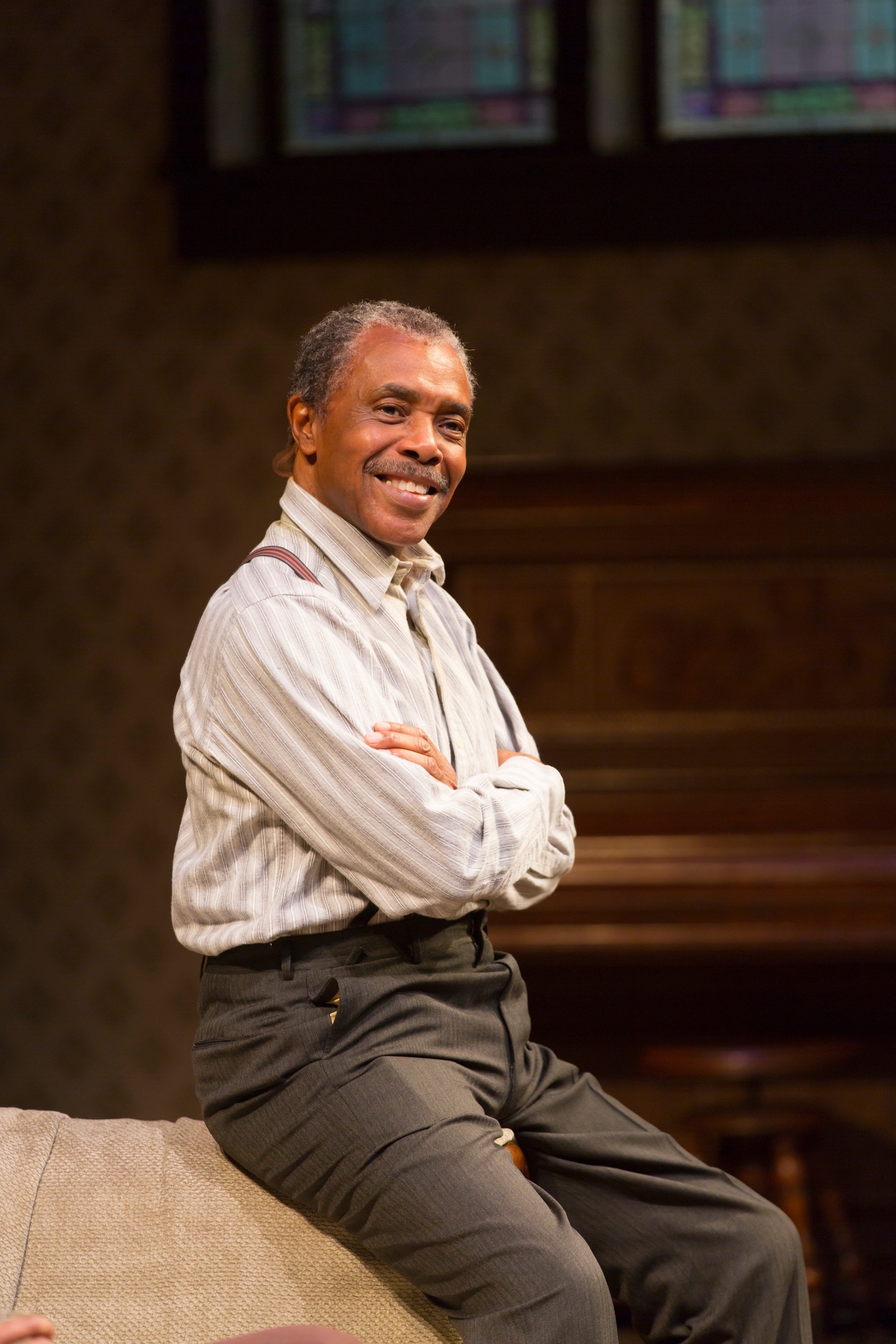

Martin (Chandler Williams)

Such is also the case with Betty (Mia Dillon, now playing her own age), who has a deliberate look of Thatcher about her, but is much more liberal. She takes us into her confidence about achieving orgasm manually, fully in the spirit of Our Bodies, Our Selves. Meanwhile, Edward (Tom Pecinka) is a gardener in the local park—where all bring their children to tire themselves out—who is trying to be a “wife” to Gerry (William John Austin), a rather feckless young man who prefers to enjoy a liberated gay lifestyle.

Lin (Sarah Lemp), Victoria (Emily Gunyou Halaas), Edward (Tom Pecinka) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

The aspect of Act Two that never completely jells is the effort to find some common ground for all these inter-relations. Certain moments, such as the song the entire cast sings, seem almost a parody of togetherness, though Williamson is unwilling to satirize progressiveness the way Act One easily satirizes patriarchy. And yet there’s no escaping the fact that seeing same-sex couples as boring—as couples—as hetero couples often are, while it may help support what must once have been a striking notion—that couples are much the same, regardless of what sort of pairing constitutes them—doesn’t make for intriguing theater. It doesn’t help that in Act Two only Dold is still playing against type. The other actors are in roles they might be cast for in conventional casting. Perhaps it’s time to shake-up casting a bit further.

The reappearance of certain figures from Act One in the play’s conclusion makes for a surprisingly fond return. Without being sentimental in effect, the final note arrives as a kind of détente with previous generations: while no doubt at a loss about how the world would change, they may at least be allowed the dignity of their historical situation. It helps, of course, that Dold’s Clive and Pecinka’s Betty are so charismatic they seem almost archetypal. Or is that just a way of saying that some things never change?

Mrs. Sanders (Sarah Lemp), Clive (Mark H. Dold) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Cloud 9

By Caryl Churchill

Directed by Elizabeth Williamson

Scenic Design: Nick Vaughan; Costume Design: Ilona Somogyi; Lighting Design: York Kennedy; Sound Design & Original Composition: Andre Pluess; Wig & Hair Design: Cookie Jordan; Dramaturg: Fiona Kyle; Fight Choreographer: Greg Webster; Vocal Coach: Ben Furey; Production Stage Manager: Denise Cardarelli; Assistant Stage Manager: Ellen Goldberg; Casting: Jack Bowden, CSA, Binder Casting

Cast: William John Austin; Mark H. Dold; Mia Dillon; Emily Gunyou Halaas; Sarah Lemp; Tom Pecinka; Chandler Williams

Hartford Stage

February 23-March 19, 2017