Making It Work

Review of Clyde’s, TheaterWorks Hartford

Lynn Nottage, two-time Pulitzer-winner for her plays, keeps it lighter than usual—and shorter!—in Clyde’s, more or less a sit-com with some serious overtones, now playing at TheaterWorks. The show, at 95 minutes, is more condensed than well-known Nottage plays like Sweat and Intimate Apparel, but, like them, explores a particular working world with great fidelity to the kind of lives lived there. In this case, it’s a greasy spoon called Clyde’s, a favorite with truckers, where Clyde (Latonia Phipps) lords it over a crack kitchen staff who have all served time in prison and who all dream of better things.

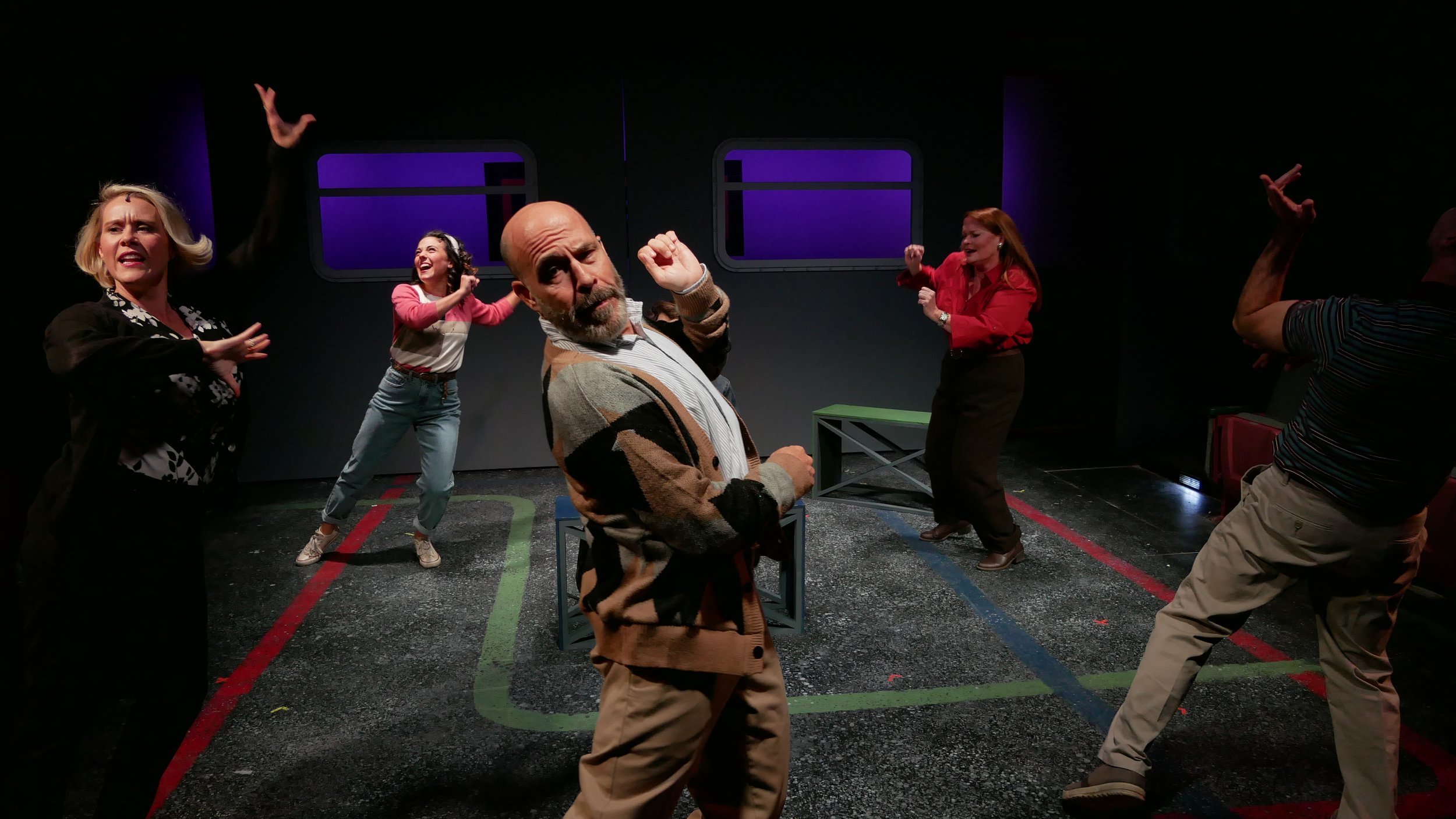

Directed by Mikael Burke with wonderful economy of movement on a small set, one of the show’s great attractions is how this deft ensemble maneuvers the very detailed and well-though-out kitchen area designed by Collette Pollard. It’s great theater and it’s a delight to experience the kitchen staff’s efforts to satisfy the churlish Clyde while also working through all their various issues.

Letitia (Ayanna Bria Bakari), Rafael (Samuel María Gómez), Jason (David T. Patterson) in Lynn Nottage’s Clyde’s at TheaterWorks Hartford, directed by Mikael Burke (photo by Mike Marques)

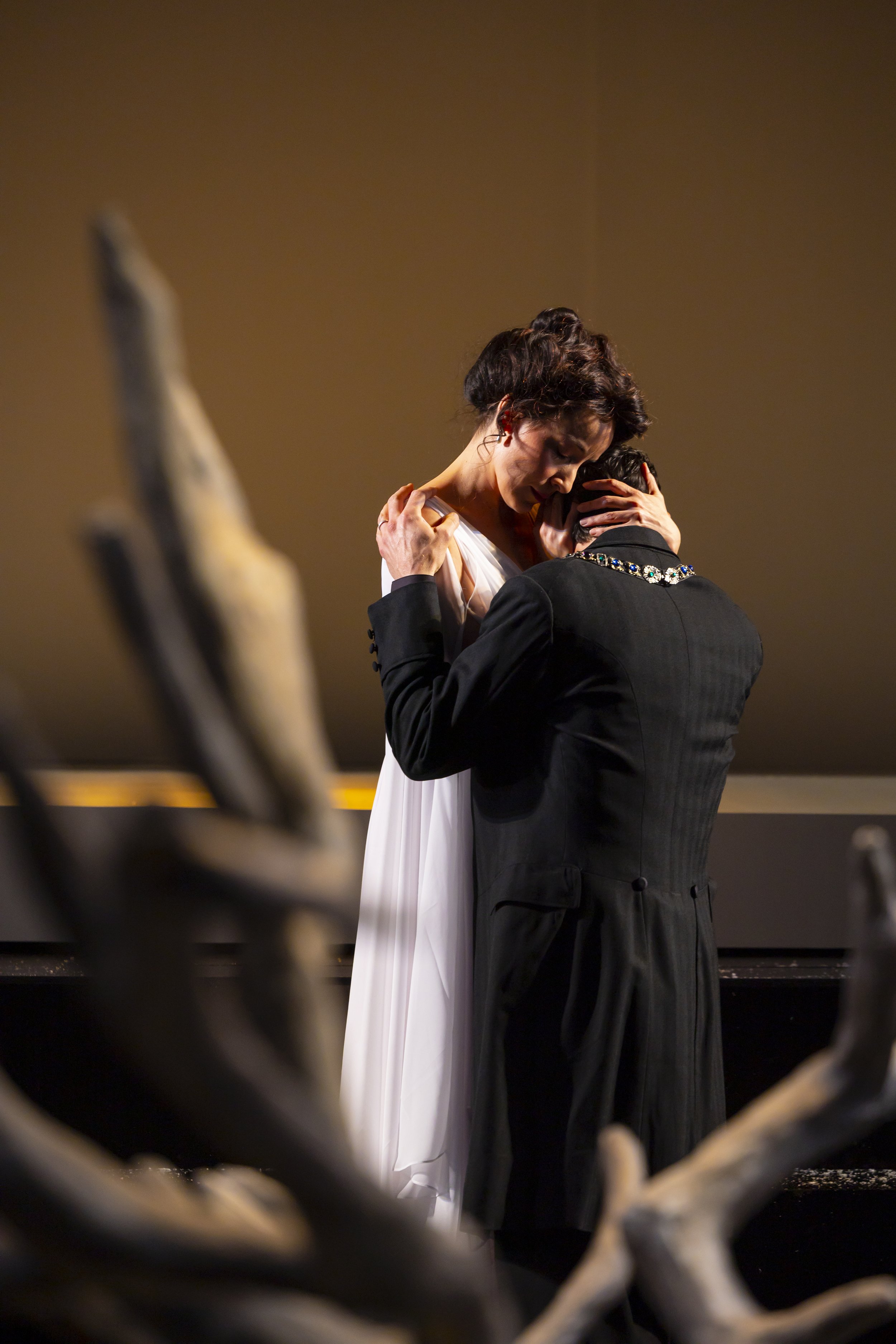

There may be a romance blooming between romantic Rafael (Samuel María Gómez)—at least if he has his way—and more down-to-earth Letitia (Kashayna Johnson, filling in for Ayanna Bria Bakari the night I saw the show); new employee Jason (David T. Patterson), replete with White Supremacist tattoos apt to aggravate this non-white staff, has to find his footing and, though by his own admission prone to violence, becomes something of a placid devotee of Montrellous (Michael Chenevert). The eldest, Montrellous, a kind of guru of the sandwich board, is out to prove that freedom is a question of the right choices, which extends from how one lives to what one eats: the right bread, the right ingredients, the right condiments. Indeed, much of the dialogue will be enough to make any foodie’s mouth water (my advice, have at least a decent snack before you see the show). Montrellous’ philosophy is the basis for a kind of holistic approach to work and eating that may allow his fellow workers to rise above Clyde’s ongoing disparagement.

Rafael (Samuel Maria Gomez), Jason (David T. Patterson), Montrellous (Michael Chenevert) in Lynn Nottage’s Clyde’s at TheaterWorks Hartford (photo by Mike Marques)

Having said all that, there’s not a lot more to say, in terms of story. Which is why I mentioned “sit-com”: the predominant feeling is that we are spending time with these characters, getting to know them as they get to know each other and (as in your favorite workplace comedy) what we learn will be sometimes amusing—as for instance, Rafael’s BB gun bank hold-up—and sometimes wrenching, as for instance Montrellous’ tale of a bad decision followed by a real act of sacrifice. The main plot point, I’d say, is whether or not Clyde will relent and actually try one of Montrellous’s unique sandwich productions.

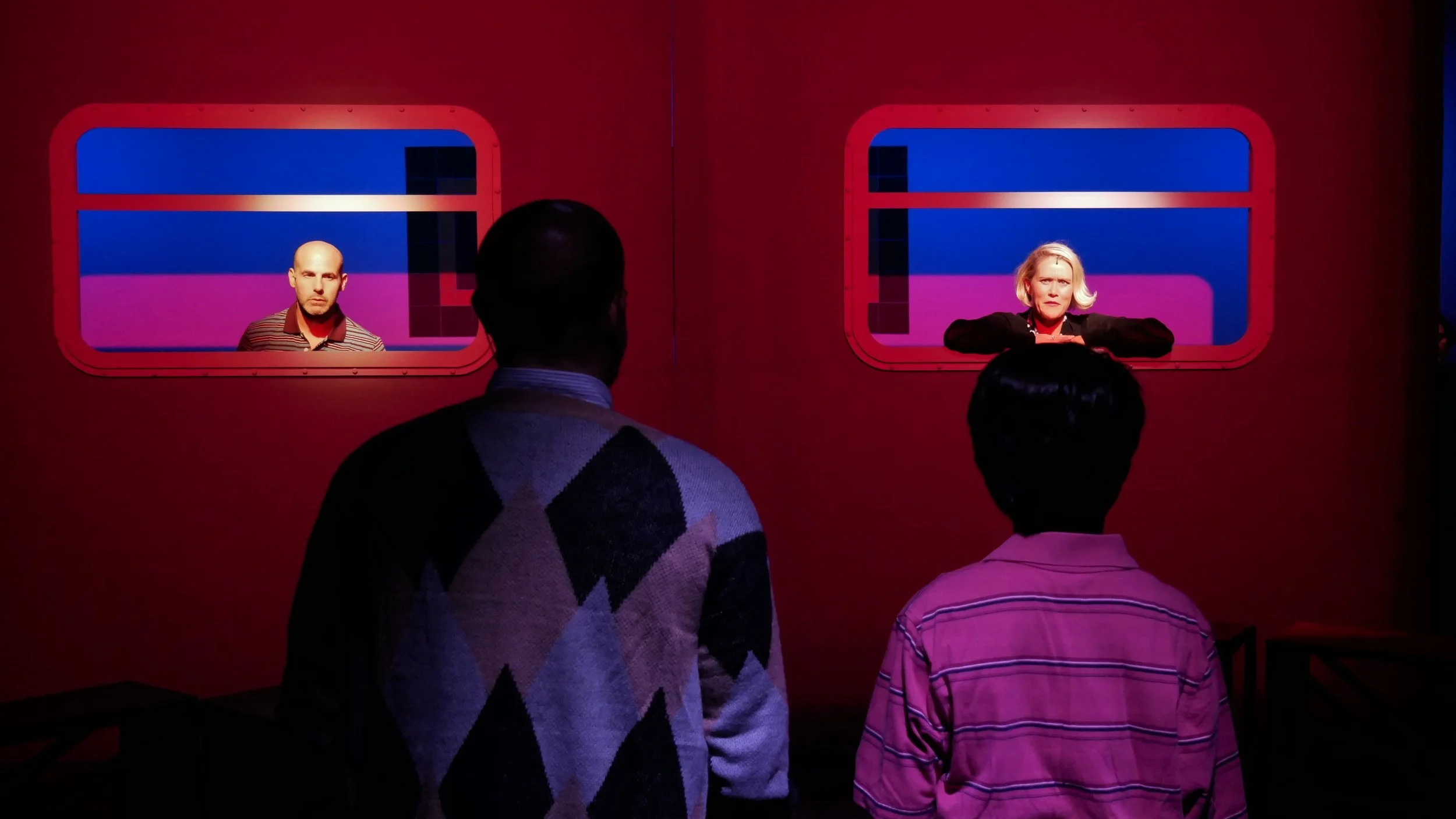

Clyde constantly puts down the crew—individually and collectively—and won’t entertain any notion that they are earning respect (not even after a newspaper write-up designates the kitchen’s productions as “sublime”) nor that any of them should have any feeling but a squalid sort of humble gratitude to her for giving them jobs and keeping them on. She’s a bully and an asshole and she loves it. Latonia Phipps luxuriates in the part but I have to say it got a bit one-note. It may be the point that Clyde doesn’t soften or sympathize (“I don’t do pity,” she boasts), but that only means we—like her employees—get sick of her that much quicker. In the words of that Nobel Laureate: “I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes: you’d know what a drag it is to see you.” (The only thing that makes us glad to see Clyde again? the costume changes! Alexis Carrie, Costumes.)

Clyde (Latonia Phipps) in Lynn Nottage’s Clyde’s at TheaterWorks Hartford (photo by Mike Marques)

But aren’t bosses often a drag? I can attest it’s so, and so it is here. Do we like the other characters? Yes, and it’s fun seeing/hearing who gets feedback—as cheers, laughs, applause—from the live audience. That “you are there” element works to great effect in TheaterWorks’ small theater and small but very lively stage. I’ll say my favorite character the night I saw the show was Kashayna Johnson’s Letitia (wonderfully filing in as an understudy); she has the best vantage on her co-workers, seeming to have the insight to grasp who they really are and who they’re trying to become, even as she herself is working to be better. She’s the soul of the place even more than Montrellous. As the latter, Chenevert has the requisite thoughtfulness and measured movements of a man who could’ve been so much more and might yet be, but his detachment doesn’t make him as sympathetic. Gómez's Rafael is winning and outgoing, and his outbursts of feeling do a lot to drive up the drama. As Jason, Patterson broods well but also has a great sense of comic timing, making Jason’s arc of change the most fun to watch.

But don’t take my word for it: get into TheaterWorks and spend some time watching this crew for yourself—if you can tear yourself away from the latest from Christopher Nolan and Greta Gerwig. Anyway, those films will likely be here for weeks. Clyde’s has been extended but only has one more week left!

Clyde’s

By Lynn Nottage

Directed by Mikael Burke

Set Design: Collette Pollard; Costume Design: Alexis Carrie; Lighting Design: Eric Watkins; Sound Design: Christie Chiles Twillie; Stage Manager: Nicole Wiegert; Associate Set Design: Delena Bradley; Intimacy Coordinator: Marie C. Percy; Casting Director: TBD Casting/ Stephanie Yankwitt, CSA

Cast: Ayanna Bria Bakari, Michael Chenevert, Samuel María Gómez, Kashayna Johnson, David T. Patterson, Latonia Phipps

TheaterWorks Hartford

July 7-30, 2023, extended run to August 5th