Review of Primary Trust, TheaterWorks, Hartford

Eboni Booth’s Primary Trust, winner of the Pulitzer in Drama for 2024, gives us a story of contemporary trauma that is more Frank Capra than Franz Kafka. And that in itself is refreshing. Directed by Jennifer Chang at TheaterWorks Hartford with a commanding sense of how to use the playing space for maximum effect, Primary Trust is an energetic feel-good play in which “the little guy” manages to navigate the minefield of everyday life without losing his dignity, much. How often does that happen?

As a note on the setting in the playbill reads: “Cranberry, New York: A medium-sized suburb of Rochester. Before smartphones.” It’s the last line that is so telling, as it not only puts the action back there before 2007, but before the reach of media via the phone became ubiquitous and incessant. As the singer Greg Brown puts it, “People used to spend quite a bit of time alone.” Remember?

Kenneth (Justin Weaks) in Primary Trust by Eboni Booth, TheaterWorks Hartford; photo by Mike Marques

The plot point, though, is that even when our hero, a young Black man named Kenneth (Justin Weaks), is alone he’s not really alone. As we learn early, he has an almost constant companion: an imaginary middle-aged friend called Bert (Samuel Stricklen). The interplay between the two is the main focus in the early going and when we learn of Bert’s phantasmal status we have to recalibrate a little. Because without Bert, with whom Kenneth haunts a tiki bar called Wally’s, downing mai tais during the two-for-one happy hour, Kenneth has only his job at a bookstore. And when the store’s genial owner, Sam (a quick study in type by Ricardo Chavira), has to sell out to afford a necessary operation, which also requires moving to the dry atmosphere of Arizona—Kenneth’s got nothing. But Bert.

Corinna (Hilary Ward), Kenneth (Justin Weaks) in Primary Trust by Eboni Booth at TheaterWorks Hartford; photo by Mike Marques

As the story develops—pushed along by Kenneth sharing his story in direct address to the audience—we see Kenneth learn to navigate life on his own. And that means talking to people who, unlike Bert and the audience, are actually in scenes with him. Chiefly, that’s a string of waitresses/waiters at Wally’s, all played by Hilary Ward with a zestful rendering of different attitudes, dialects, and levels of professionalism. Eventually, the friendly and interested Corrina emerges from the pack and makes a chance suggestion about job prospects at a local bank (Kenneth’s deceased mother had been an employee at a different bank). Kenneth, who previously had a social worker who found him a job, takes the initiative and, with Bert’s backing, goes to a job interview where he meets the generally sympathetic Clay (Ricardo Chavira as an enthusiastic former high school football star), gets hired, and soon begins to succeed on the job.

Clay (Ricardo Chavira), Bert (Samuel Stricklen), Kenneth (Justin Weaks) in Primary Trust by Eboni Booth at TheaterWorks Hartford; photo by Mike Marques

Interestingly, Kenneth’s traumatic backstory, which features the original for Bert, is not told to the audience, but rather to Corrina on an impromptu night out at a French restaurant. As we might expect, further trauma will surface when Kenneth comes to understand that having real people in his life makes having an imaginary companion more difficult. While the more dramatic touches in the play can feel a bit manipulative, the likeability of all the characters we meet—including a slew of eager to-be-pleased bank customers (Ward again)—keeps the play bouncing along in a mostly cheerful groove.

Corrina (Hilary Ward), Kenneth (Justin Weaks) in Primary Trust by Eboni Booth at TheaterWorks Hartford; photo by Mike Marques

The fact of personal trauma is treated seriously, and the play’s main strength is the way Booth and Chang make theater of the sharing of stories and telling truths as a mainstay of fellowship. We see how relations between employer and employee, or between customer and worker, can be cordial rather than adversarial. Primary Trust takes its title from the name of the bank where Kenneth works, but it also alludes to the idea that trust is primary to any friendship. We may decide for ourselves whether the virtual world has helped to foster or undermine such trust. To say nothing of the political climate the internet aggravates.

The entire cast is engaging and makes each character—no matter how briefly glimpsed—come alive vividly. The more extended roles—Corrina, Clay, Bert—let us learn more about Kenneth by reflection, as we come to know him better by the kinds of interactions he inspires. As Kenneth, Justin Weaks’s thoughtful and touching performance works through a gripping emotional range—at times, reserved and closed off, at other times effusive and emotional. Kenneth is the heart and soul of the play, a young man already sorely tried by life who helps us realize that just getting by can be a great triumph. As we watch, his joy in life becomes ours.

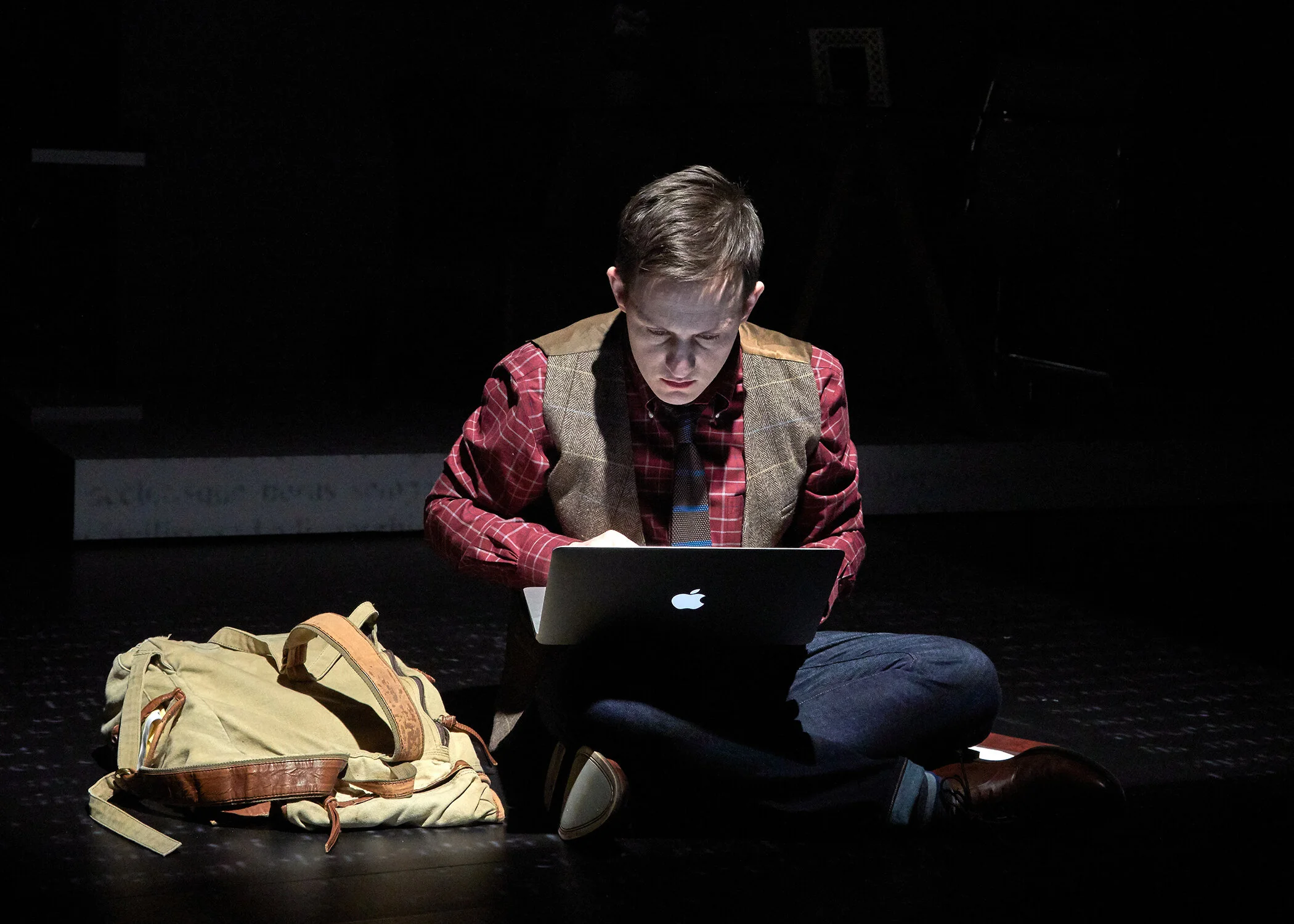

Kenneth (Justin Weaks), Bert (Samuel Stricklen) in Primary Trust by Eboni Booth, at TheaterWorks Hartford; photo by Mike Marques

The staging here is very fast and effective, as in most TheaterWorks shows, with serviceable props and backdrops that quickly shift the scenes, letting us feel we’re becoming at-home in Kenneth’s mind, finding out that empathy can be a magic door into another world.

Primary Trust

By Eboni Booth

Directed by Jennifer Chang

Set Design: Nicholas Ponting; Costume Design: Danielle Preston; Lighting Design: Bryan Ealey; Sound Design: Frederick Kennedy; Wig Design: Earon Chew Healey; Associate Director: Moira O’Sullivan; Dialect Coach: Jennifer Scapetis-Tycer; Stage Manager: Tom Kosis

Cast: Ricardo Chavira, Samuel Stricklen, Hilary Ward, Justin Weaks

TheaterWorks, Hartford

April 10-May 11, 2025