Review of Sylvia, Music Theatre of Connecticut

It’s Valentine’s Day and if your sense of romance may have stalled somewhat over the years, maybe Sylvia, A.R. Gurney’s romantic comedy now playing at MTC, Norwalk, has the answer: get a dog!

Directed by Kevin Connors, Gurney’s play is affable and light. There may be a sense in which the midlife crisis faced by Greg (Dennis Holland) is symptomatic of something darker, but, in general, the play assumes that long-married couples may find themselves confronted by new tastes or long-suppressed desires or dissatisfactions that could manifest in many ways. Greg and Kate (Carole Dell’Aquila) have been together twenty years and the crisis comes in the form of an affectionate stray that Greg encountered in a park and brings home, expecting Kate to just lie down and roll over, so to speak.

Sylvia (Bethany Fitzgerald) in A.R. Gurney’s Sylvia at MTC (photo by Alex Mongillo)

The dog wears a collar with its name, Sylvia, and she is a bundle of energy and, thanks to the miracle of theater, we are privy to her thoughts. That aspect of the play—the verbalized reactions of a frisky dog—is a crowd-pleaser, however obvious. As played by Bethany Fitzgerald, Sylvia is indeed a charming pet and anyone who might look askance at a woman playing a dog shouldn’t judge until they see it done. She looks upon Greg as “God,” aims to please, gets excited by each new arrival at the apartment, wants nothing more than to stretch out upon furniture, and speaks with an intense immediacy, suitable to an animal that lives in the moment. She’s also funny and lovable and makes the play work. Yes, the dog does indeed wag the tale.

Sylvia (Bethany Fitzgerald), Kate (Carole Dell’Aquila) in A.R. Gurney’s Sylvia at MTC (photo by Alex Mongillo)

Less obvious and somewhat less successful is how to stretch such a slight premise into a two hour play, with intermission. This is not easy to do as Gurney hasn’t given Greg’s wife much of a role. Dell’Aquila manages to seem sensible rather than a wet blanket, mostly. But whether or not she has your sympathy may have something to do with how you feel about dogs, and middle-aged men, and the possibilities in life afforded to post-menopausal women. Early on, it seems we might find fun in her occupation as a high school teacher of Shakespeare, so that when she offers “thus bad begins and worse remains behind,” we might catch ourselves hoping that more Shakespearean lines or tropes will percolate through the play. Not so much; Greg never even manages to play on his wife’s sympathies by intoning “What joy is joy if Silvia be not by?” And yet that is where he’s at, you might say.

Sylvia (Bethany Fitzgerald), Greg (Dennis Holland) in A.R. Gurney’s Sylvia at MTC (photo by Alex Mongillo)

Sylvia, in her unquestioning affection, helps her master deal with his current malaise: a job that has passed him by for younger colleagues with younger ambitions, an empty nest; and a wife who is done with the “the dog phase” of her life, much as she is with the children-raising part, and, almost, the stand-by-your-man part. For her, it’s a time to get on with things she wants to do—like research; for Greg, it’s a time in which companionship of some kind is needed. While we might expect that his new-found infatuation might be a younger woman, the play cleverly assumes that a dog can be more appealing than a new paramour. If there’s a bit of winking at the notion of bestiality in Act Two, it certainly isn’t played up in this production.

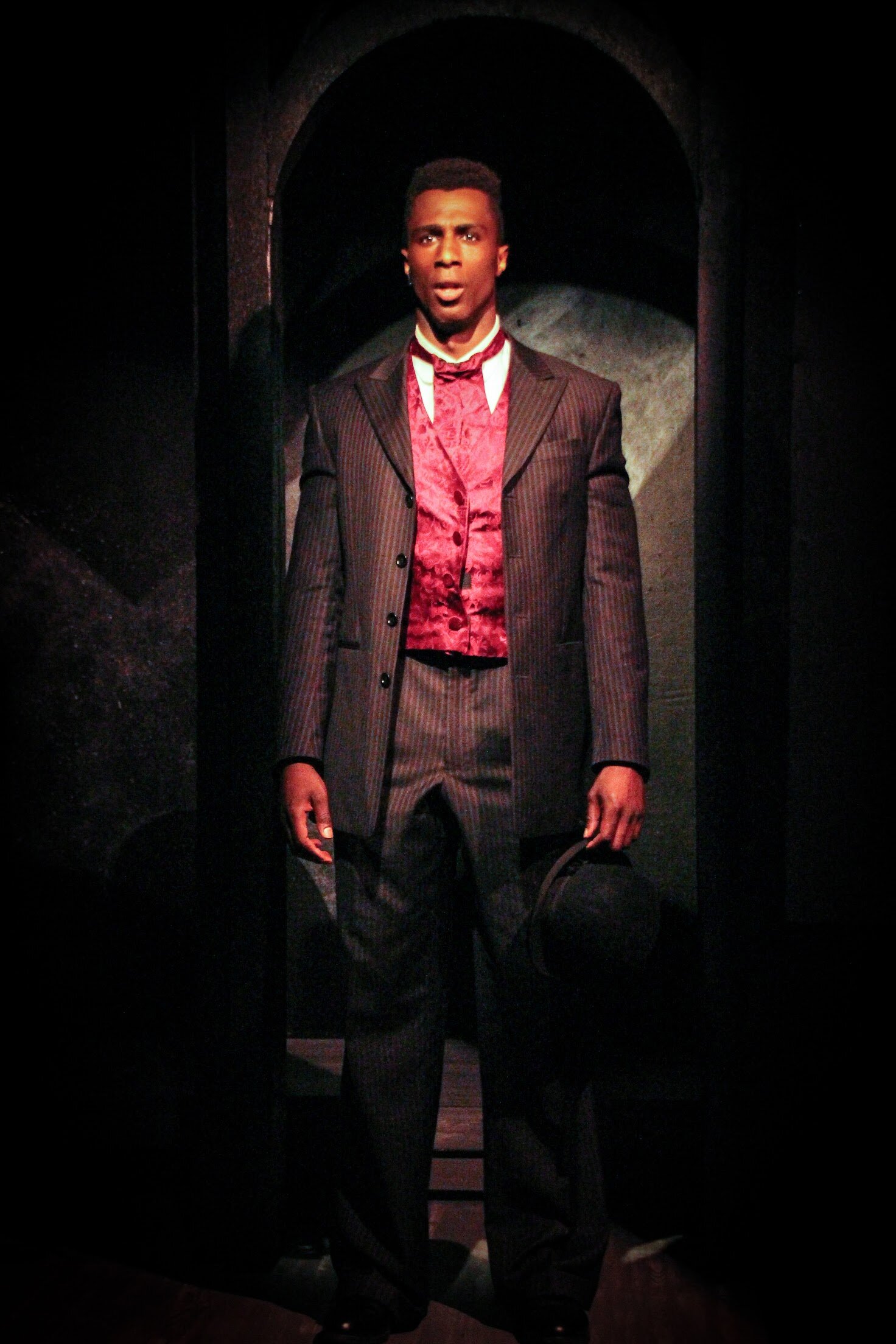

Tom (Jim Schilling), Greg (Dennis Holland) in A.R. Gurney’s Sylvia at MTC (photo by Alex Mongillo)

Connors draws upon the comic abilities of MTC regular Jim Schilling to create three different characters who intervene in the hi-jinx. One—Phyllis—is a tony lady friend of Kate’s, played for laughs as a not so surreptitious tippler; another—Leslie—is a counselor of fluid gender who seems to suspect the worst of Greg’s urges for Sylvia and recommends that Kate work up the full revenge-fury of a wronged wife. As Tom, he’s a buddy-buddy bench-warmer at Dog Hill (a park where city-folk can let their canines cavort) with a male dog of his own, and the eventual coupling of Sylvia and Bowser, off-stage, might illicit a variety of comic reactions. Schilling and Holland play it mild, at every point letting us off the hook of having to view Sylvia sexually. And that’s helped by Fitzgerald’s refusal to play Sylvia as, well, kittenish. Sylvia, even when in heat, is matter-of-fact and forthright. When she curses out a cat, she’s foul-mouthed but only then, and it’s hilarious.

And that’s important because Greg is a rather buttoned-up guy and so Sylvia may well be his perfect pet. Eventually, Kate seems to see this and grudgingly allows him to have some quality time with the dog she wants him to give away. In Act Two she devises a plan that should spell the end of the spell, and we face an effectively emotional farewell. At this point, Sylvia does sound like a young woman led on by a philandering married man’s promises of a permanent relationship, but that easy identification doesn’t undermine the feeling of actual regret, which Holland depicts well.

Greg (Dennis Holland), Sylvia (Bethany Fitzgerald) in A.R. Gurney’s Sylvia at MTC (photo by Alex Mongillo)

Taking place in a tasteful living-room, with, on a raised space behind, some benches with an attractive 3-D city skyline as backdrop, MTC’s Sylvia is—like the word of praise for many a mutt—companionable. If it stirs thoughts about the mystery of attachment, all the better. A dog, after all, can never be accused of ulterior motives. She might say, with the author George Sand, “there is only one happiness in life, to love and be loved.” And that two random, interspecies strangers should meet and find that is the joy and sorrow of Sylvia. Don’t be afraid to love.

Sylvia (Bethany Fitzgerald) in A.R. Gurney’s Sylvia at MTC (photo by Alex Mongillo)

Sylvia

By A.R. Gurney

Directed by Kevin Connors

Scenic Design: Jessie Lizotte; Lighting Design: RJ Romeo; Costume Design: Diane Vanderkroef; Sound Design: Will Atkin; Prop Design: Merrie Deitch; Fight Staging: Dan O’Driscoll; Stage Manager: Gary Betsworth

Cast: Carole Dell’Aquila, Bethany Fitzgerald, Dennis Holland, Jim Schilling

Music Theatre of Connecticut

February 7-23, 2020