Review of Elon Musk and the Plan to Blow Up Mars The Musical, Yale Cabaret

In Liam Bellman-Sharpe’s sci-fi musical, Elon Musk and the Plan to Blow Up Mars, Elon Musk, the entrepreneur behind Tesla, SpaceX, and other tech concerns, is a man with a mission. After commiserating with a group of billionaires—including Jeff Bezos (Eli Pauley)—who confide to us that it’s great to be rich but it’s hard to be rich, Musk (David Mitsch) comes forward with a song describing his love of Mars, a view that seems true of the actual Musk with his dream of a colony there someday.

It comes as a surprise, then, when the crew of a spaceflight to Mars—Captain (Nomè SiDone), Eyes (Madeline Seidman), Hands (Maal Imani West), Navigator (Isuri Wijesundara)—learn that Musk is aboard, that he chartered the flight, and that he has plans to destroy the Earth’s nearest neighbor. Musk’s change of heart—from colonizing Mars to destroying it—comes via “the Voice of the Night Sky,” a kind of burning-bush moment that converts Musk from a proselytizer for humanity’s destiny among the stars to a kind of interplanetary terrorist, willing to obliterate the red planet to save the blue one.

The absurdity of the musical’s plot could be said to be an intentional mirroring of the absurdity of financial titans becoming space-age saviors, but the show also features the kind of daffy shenanigans that have been the basis of grade B sci-fi films for decades. And that makes for some very entertaining bits, such as Patrick Young as a quintessential mad scientist enlisted by Musk to plumb the possibilities of antimatter, which is key to his scheme, and some offbeat satirical science presentations.

In the first, Maal Imani West delivers a “thought experiment” on how scientific breakthroughs, in affording new products, can solve problems that are more lucrative to leave unsolved. Using dentures as her example, and aided by great graphics by projection designers Erin Sullivan and Hannah Tran, West reflects on how a demand for new teeth could lead to plans to undermine tooth and bone to make the general populace dependent on new products to save them from conditions created by the breakthrough itself. Sound familiar?

Bellman-Sharpe’s target in all this isn’t simply the absurd wealth and power of Musk or Bezos but the system that has enriched and empowered them. And if their grasp of capitalist principles weren’t enough, we’re faced with their space manias as a prospect of what the rich may do when they decide they needn’t be stuck on this woefully mismanaged rock with the rest of us. As Educational Host (Isuri Wijesundra) delivers a bouncy science lesson on “slime molds” and their ability to proliferate and form bonds with the complexity “of the interstate system,” Bezos is desperately trying to reach Musk to dissuade him from making Mars extinct. The dovetailing of Bezos’ fear of capitalism imploding and the Host’s upbeat ditty about the wonders of single-cell lifeforms works as an ironic commentary on how far we’ve come—in evolutionary terms—and how far we can fall.

While not quite a full musical in its lack of a big finale musical number, Elon Musk . . . does boast the requisite romantic interlude. Here it’s a wonderfully comic and spirited encounter between Eyes and a being made of Antimatter (Patrick Falcon). The pas de deux and duet (Antimatter’s lovely voice provided by Taylor Hoffman) puts both heart into the show and a spanner in the works of Musk’s plan, as Eyes, now in love with Antimatter, wants to preserve the creature at the cost of not destroying Mars.

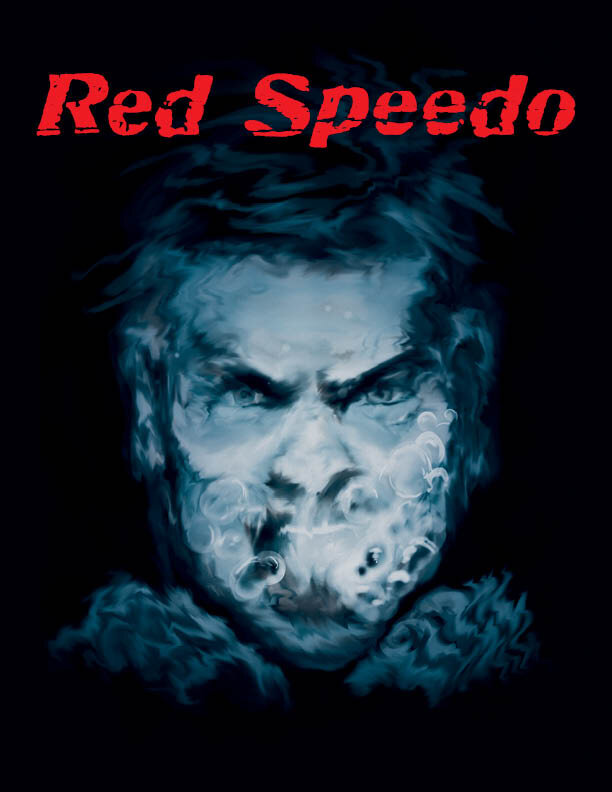

The show’s oddity is its saving grace, but its narrative arc tends to be a bit hodgepodge, including a vaudeville routine about speeding in space and a song by a Drag King (Maal Imani West in male drag that smacks a bit of Little Richard, with a sumptuous smoking jacket) about the world not being a place to bring children into. Thanks to West’s great singing voice, the song is a standout even if we might wonder how it fits in, exactly.

All in all, one might say, that whether you’re trying to destroy a planet or to save one, a kitchen-sink approach is best, and one wouldn’t want to underestimate the enormous profits to be made by capitalizing on either project. In Elon Musk and the Plan to Blow Up Mars the Musical, science as a means to get rich and science as a means to save the Earth and/or mankind has reached its tipping point. That timely reflection and the possibilities of a sci-fi musical with big name power players in its dramatis personae certainly gives Bellman-Sharpe’s play remarkable potential. Per aspera ad astra.

Elon Musk and the Plan to Blow Up Mars the Musical

Music, Text, and Direction by Liam Bellman-Sharpe

Choreographer: Mariel Pettee; Set Designer: Alex McGargar; Costume Designer: David Mitsch; Lighting Designer: Noel Nichols; Sound System Designer: James T. McLoughlin; Projections Designer: Erin Sullivan; Associate Projections Designer: Hannah Tran; Associate Stage Manager: Kevin Jinghong Zhu; Dramaturg: Henriette Rietveld; Technical Director: Jonathan Jolly; Producer: Carl Holvick; Stage Manager: Sam Tirrell

Cast: Patrick Ball, Patrick Falcon, David Mitsch, Eli Pauley, Madeline Seidman, Nomè SiDone, Bailey Trierweiler, Maal Imani West, Isuri Wijesundara, Patrick Young

Musicians: Sharon Ahn, keyboards; Roberto Granados, guitar (alternate); Thomas Hagen, drums; Satchel Henneman, guitar; Taylor Hoffman, vocals; Paul Mortilla, violin; Adin Ring, bass

Yale Cabaret

January 23-25, 2020