Review of Tommy, Seven Angels Theatre

This year marks fifty years since The Who released their “rock opera” Tommy. Composed primarily by Pete Townshend, the band’s lead guitarist, the album told a story in song over two LPs. The story could feel a bit sketchy at times, but the main gist was that a young boy—Tommy—witnesses an act of violence and suffers a traumatic reaction: he goes deaf, dumb, and blind in defense. But that defense makes him highly vulnerable to certain unsavory characters around him, such as “wicked Uncle Ernie” and cousin Kevin, a bully. As Tommy becomes a teen he astounds the locals with his incredible skill at playing pinball. The eventual realization that his affliction is psychosomatic leads to a “miracle cure,” and he becomes “a sensation” as the spokesman for the value of an inner life cut off from the outer world. He founds a “holiday camp” where kids can experience sensory deprivation and learn to play pinball—until his followers become a mob in revolt and destroy the place, leaving Tommy to sing beseechingly to his own higher self, or to God, or to a guru (Townshend at the time was a follower of Meher Baba, an Avatar of God).

That, more or less, is the story that was translated into a film by Ken Russell in 1975. Then, in the early 1990s, Townshend with Des McAnuff, wrote the Book for a Broadway version. Called The Who’s Tommy, the show won five Tony awards and was nominated for an additional six. In this version, Tommy suffers the same affliction but the ending is much different. Instead it’s as if, at the end of Jesus Christ Superstar, the crowd calling for Christ’s crucifixion said “to hell with it” and left, and Pilate, relieved, sent Jesus home to his family and friends. In other words, Jesus Christ Superstar—the other great rock opera of the period—has to stick to the Gospel. The Who’s album isn’t gospel, and this “kinder, gentler” Tommy seems born of the 1990s’ need to remake the forces of the Sixties in its own image. Tommy doesn’t even get to try acid in this version!

Well, that’s all water under the bridge, or show-biz, we might say. Though a reminder of what was may be worthwhile since many more people—who might be vague about who The Who were—are likely to have seen the Townshend/McAnuff version of Tommy, which is now playing at Seven Angels Theatre in Waterbury, directed by Janine Molinari, through May 19.

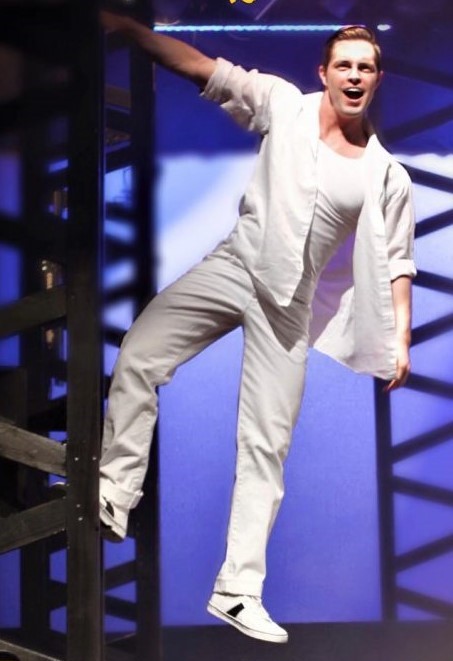

Tommy (Garrison Carpenter) (photo by Paul Roth)

Even without the “flying by Foy” and the razzle-dazzle set constructions of McAnuff’s staging, Tommy at Seven Angels is still “a sensation.” The roles of Tommy as a 4 year old and a 10 year old are handled by RJ Vercellone and Brendan Reilly, respectively, and they are perfectly cast. Tommy as, at first, a vision seen by young Tommy, and then as the grown-up version, is energetically enacted by Garrison Carpenter, who has the looks and the voice to put across Tommy’s pop godhood. He hangs from scenery and struts and beseeches and takes us on “the amazing journey” with a cockiness that never flags.

Janine Molinari’s choreography is crisp and tight and matches well the propulsive rhythms of Townshend’s score. The songs are some of the songwriter’s best in their deliberate recall of show tunes mixed with the grandeur of hymns. “Pinball Wizard,” the first act closer—and the LP’s hit—is a big rave-up as Tommy seems to have found his calling, his skill praised by others in John-the-Baptist-like terms.

clockwise from top: Tommy (Garrison Carpenter), Mrs. Walker (Jillian Jarrett), 4-year-old Tommy (RJ Vercellone), Captain Walker (Ryan Bauer-Walsh) (photo by Paul Roth)

As Tommy’s mother, Mrs. Walker, Jillian Jarrett is plaintive when need be but also handles the lyrical “I Believe My Own Eyes,” in duet with Ryan Bauer-Walsh as Captain Walker, her husband, and mounts well the tension of “Smash the Mirror.” Bauer-Walsh has several fine moments where the father’s concern for his estranged son are quite tangible. Adam Ross Glickman brings such vocal skill and character-actor panache to Uncle Ernie it’s a shame there aren’t more songs for him. Likewise Keisha Gilles’ show-stopping Acid Queen: she’s such a presence we might find ourselves hoping she’ll break into character again when she’s onstage briefly as a nurse. As the Specialist, Will Carey has a certain wild-eyed charm singing “Go to the Mirror, Boy,” (one of my favorite tunes in the show).

Speaking of favorite tunes, I’ll never be able to acclimatize myself to what becomes of “Sally Simpson”—originally a wonderfully witty set-piece narrative of a fan’s ill-fated effort to get close to her idol, it becomes a weak gesture at a romantic interest, though Rachel Oremland does Sally full justice. Likewise, in terms of bowdlerization, “We’re Not Gonna Take It” barely recalls the nastiness of the original which makes the show’s conclusion—if you’re paying attention to the words—lacking in drama. That said, the song is a Townshend tour de force and, as it segues seamlessly into “See Me Feel Me”’s kick-out-the-jams climax, the audience—to vary the song’s lyrics—will show excitement on their feet.

And how about that band? Guitar (Jamie Sherwood), bass (Dan Kraszewski) and drums (Mark Ryan) are the heart-and-soul of The Who’s sound, here fleshed out by conductor Brent C. Mauldin on keyboard 1 and Mark Ceppetelli, associate conductor on keyboard 2, and by Renee Redman on French horn. The voices of the singers—including Jackson Mattek (Cousin Kevin) and many in the ensemble—are all plenty strong enough not to get lost in the rock, and Matt Martin’s sound design is a delight. As are Ethan Henry’s costumes of those bygone years of the post-war look morphing into teddyboys and mods. Daniel Husvar’s scenery comes and goes quickly, making the most of risers and fast changes that make the action move quick and slick.

Colorful, passionate, and still full of the weirdness of an inspired rock savant of the late Sixties, The Who’s Tommy lets Pete Townshend turn the spotlight from the stage to his fans, celebrating “you” (i.e., us) for making his career—and his greatest creation, Tommy—a success. See it, and take a bow.

The Who’s Tommy

Music and lyrics by Pete Townshend

Additional music and lyrics by John Entwhistle and Keith Moon

Book by Pete Townshend and Des McAnuff

Directed by Janine Molinari

Choreographer: Janine Molinari; Assistant Director: James Donohue; Music Director: Brent Crawford Mauldin; Assistant Choreographer: Boe Wank; Lighting Design: Doug Harry; Scenic Design: Daniel Husvar; Sound Design: Matt Martin; Costume Design: Ethan Henry; Stage Manager: T. Rick Jones

Cast: Richie Barella, Ryan Bauer-Walsh, Will Carey, Garrison Carpenter, Keisha Gilles, Adam Rose Glickman, Jillian Jarrett, Jackson Mattek, Rachel Oremland, Brendan Reilly, RJ Vercellone

Ensemble: Ryan Borgo, Eileen Cannon, Dean Cesari, Bobby Henry, Tony LaLonde, Peter Lambert, Diane Magas, Robert Melendez, Brittany Mulcahy, Patti Paganucci, Kevin L. Scarlett, Madeleine Tommins, Justin Torres

Orchestra: Brent C. Mauldin, conductor/keyboard 1; Mark Ceppetelli, associate conductor/keyboard 2; Dan Pardo and TJ Thompson, associate conductors; Marissa Levy, sub: keyboard 2; Renee Redman, French horn; Cody Halquist, sub; Jamie Sherwood, guitar; Dan Krazewski, bass; Mark Ryan, drums; Kurt Berglund, sub

Seven Angels Theatre

April 25-May 19, 2019